She was back. Thank you, God.

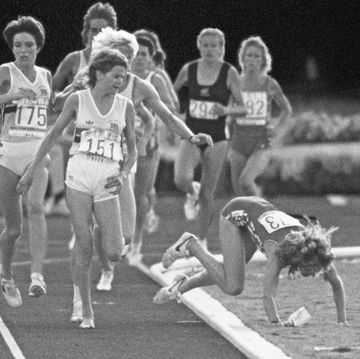

It happened at the 100-meter hurdles semifinal of the 2008 Olympic Trials. On Hayward Field in Eugene, Oregon, Kellie Wells stood in lane four, her teammate and friend Damu Cherry to her right in lane five. Eight athletes took their marks. Set. Go.

Wells exploded off the blocks with her characteristic grunt. Other hurdlers screamed. They all covered the 13 meters to the first hurdle in exactly eight steps. Wells attacked the first hurdle tied for first, extending her right leg parallel to the ground, driving her upper body forward and down, skimming the top of the 33-inch-high barrier. She snapped her right foot to the ground and whipped off the 8.5 meters to the next hurdle in three steps. The athletes were close enough to touch fingers, hook hands. By the fourth hurdle Wells was alone in first place, devouring the space between barriers to open a slight lead.

A hurdles race is about rhythm. Three steps-attack, three steps-attack. All that matters is how fast you take those three steps. When she reached hurdles 8, 9, and 10, Wells felt a downhill sensation take over. At such speed, her eyes played tricks on her. Each hurdle appeared so fast, there seemed barely room to clear it. Three steps-attack, three steps-attack. After hurdle 10, there were just 10.5 meters—five steps—to the finish line. But hurdlers cannot simply race to the line. The depth of American women hurdlers is so great and the margins of victory so slim they must hurtle themselves through it, leaning at such a pitch that they can topple into somersaults. Wells threw her head and shoulders forward and crossed the line in second place behind Cherry. Steps after the line, she looked up at the clock. Not only had she qualified for the finals, but she had also run 12.58 seconds, a PR by .13 seconds, huge in a sport where the world record is 12.21.

Wells slowed down, ecstatic. And that’s when she heard it. The sound of a grade-three hamstring tear, a complete rupture of the muscle. She collapsed, writhing with pain as her right leg cramped. Medics rushed out. They tried to straighten the leg, get her to stand, to walk. Please God, it hurts too much. They loaded her onto a stretcher and sent her to the ER. No, I have to run! During the MRI, the technician piped in the results of the final: Lolo Jones, Damu Cherry, and Dawn Harper were going to Beijing.

After the scan, Wells lay on a hospital bed while the doctor delivered his verdict. Her injury was so severe she may never run again. If she did run, it was unlikely she’d ever run fast.

Had it finally betrayed her?

The track had been her refuge, her friend, her mate since childhood. Through all the horror, it had been there for her.

Runners World Featured?

KELLIE WELLS, 29, DOES NOT HAVE A PROFESSIONAL HURDLER’S BODY. When she lines up at events, she’s easy to pick out; she’s the small one. At 5'4" and 125 pounds, she is shorter and lighter than most of her competitors, who typically stand at least 5'5". Her lithe frame is muscular, tight, and without a trace of fat, but to the uninitiated seems fitting more for a dancer than an attack machine. But that’s exactly what she is.

She is one of many. Though she captured both the Indoor and Outdoor Championships in a breakout 2011 performance, when Kellie Wells takes the blocks in Eugene this June for the Olympic Trials, she will be testing herself, and her repaired hamstring, against one of the strongest fields in history. The women’s hurdles is stacked with talent that includes Lolo Jones, winner of the 2008 Trials; Dawn Harper, 2008 Olympic gold medalist; and Danielle Carruthers, second in the 2011 World Championships. “We’ve never had this depth in the women’s 100-meter hurdles,” says Gail Devers, 45, two-time Olympic gold medalist in the 100-meter sprint, multiple world champion in the 100-meter hurdles, and self-professed grandmother of women’s hurdling. “We are six, seven, eight deep, and unfortunately, only three can make the team. The field is wide open—it’s going to be an all-out battle of who’s on it that day.”

But other than size, there is something else that separates Kellie Wells from the other machines. Raw emotion. The excitement of a kid. When she wins, she screams and jumps and falls and pops up again and hugs TV reporters. “She runs with her heart every time she steps on the track,” says Devers. “Sometimes she leaves it on the track, but every meet she does her best, and that touches the heartstrings.”

When Kellie Wells takes the blocks in Eugene this June for the Olympic Trials, many running fans will be rooting for her redemption. Should she win, they will undoubtedly be swept up in the excitement that Wells will express.

What few will understand, though, is that Wells has earned that childlike joy. Because she was denied it the first time around.

TODAY, THERE ARE NO CHILDREN PLAYING outside in the cul-de-sac neighborhood in Chesterfield, Virginia. Towering pine trees line a bluff that buffers the homes from boulevard traffic noise. Six modest, mostly split-level houses surround the circle, and a lone cedar tree stands at its apex. For the three Wells children, this is where it all began—the running, the competition, the abuse.

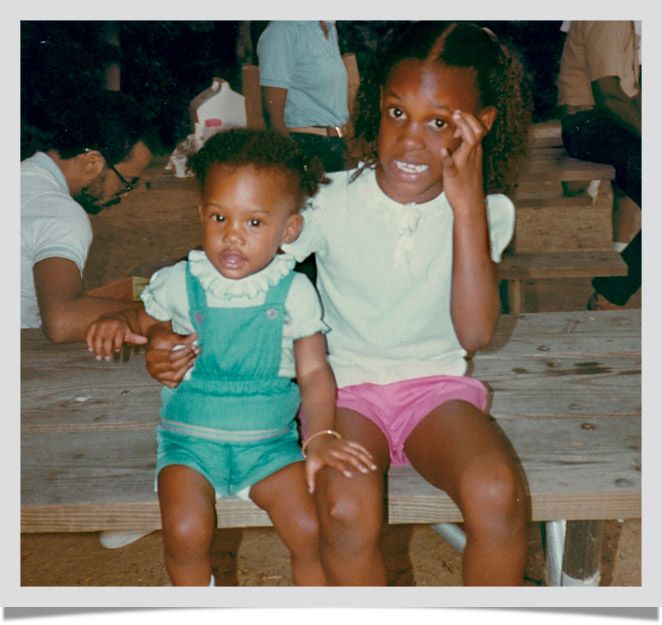

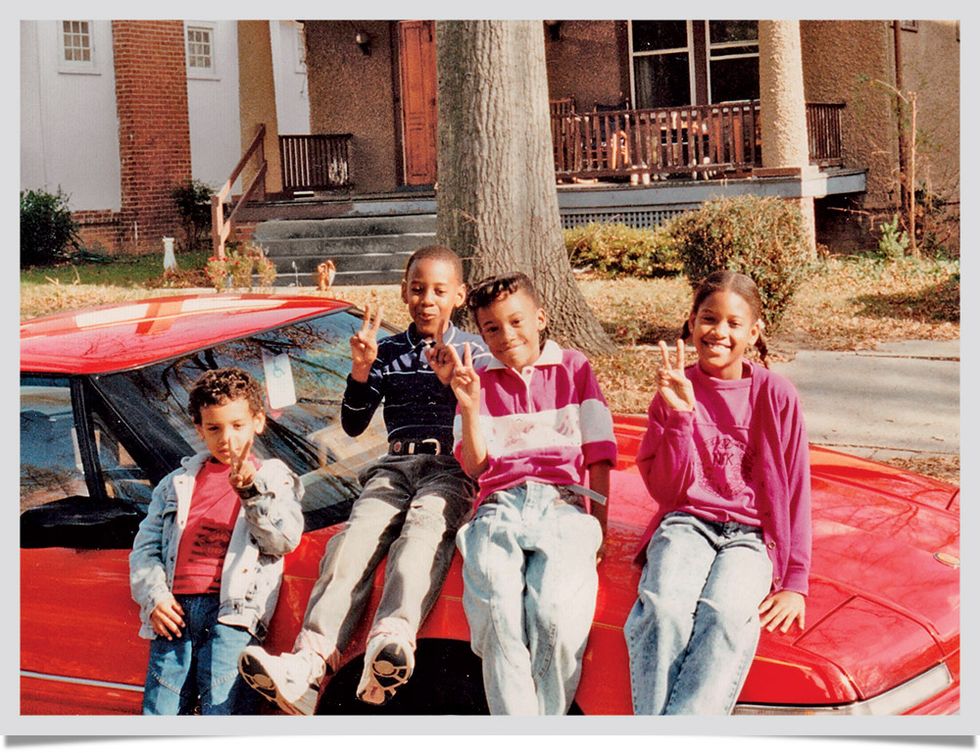

Back in the 1980s, there was always something going on in the cul-de-sac. Frisbee, football, dodgeball. Bike, egg-on-spoon, and three-legged races. But the straight sprints—they were the Big Deal. In the summer, 10 or so neighborhood kids held daily tournaments, chalking out lanes on the street, running sprints and relays using napkin holders as batons. Parents would gather and cheer from front porches. “We lived in a very competitive neighborhood,” says Tonni Wells, 35, Kellie’s older sister. “It was cutthroat. If you wanted to hang with the cul-de-sac crowd, you had to be a fast runner.”

Tonni was a fast runner. Which meant Kellie wanted to be, too. She tailed her older sister to track practice and tried to do the same drills and workouts. Kellie ran against the neighborhood boys; when she beat them, she talked trash; when she lost, she cried. “I just wasn’t into losing,” says Wells.

There was always something else going on in the cul-de-sac, too—the explosive rage of their father. A chemical engineer with a penchant for numbers, he grew irate one day watching Tonni struggle with simple math, counting out 13-plus-7 on her fingers. “He was so mad, he hit me in the chest,” she says. “I fell over backward in the chair and broke it.”

It was her mother, however, who bore the brunt of his anger. Jeanette Wells was a carefree spirit, a smart, beautiful woman who smiled when she worked out, made up dance routines on the spot, and spontaneously broke into song while shopping. She worked hard to ensure her kids could travel with the track team, go to dance class, and wear nice clothes. Arguments sometimes escalated over money, but Tonni doesn’t know what they were fighting about the time she ran inside for a Popsicle on a hot July day and found her mother cowering behind a chair, her arms raised and her nose bloody. All she knew was these people should not be together, and when she was a sophomore and Kellie was in fifth grade, her father moved out.

For a while, things were okay. Divorced life hit a rhythm; it wasn’t great, money was scarce, but Jeanette worked long hours to keep life for Tonni, Kellie, and Jason (now 27) as normal as possible. And then Jeanette met Rick.

Tall, muscular, with a head of dark curls and a persuasive, charming demeanor, Rick Gomes was a high school gym teacher and multi-sport coach. He favored Gucci sweaters, expensive cologne, and Gold’s Gym tank tops that showed off his biceps. “He was God-awful handsome,” says Tonni. And he had a reputation. Word around Tonni’s track friends was that he had a creepy way of talking to and looking at the girls. “I had a feeling, like, bad news,” Tonni says. “It was a weird premonition.”

Jeannette asked Tonni to give him a chance. And nearly a year later, the family had moved into Gomes’s house, where he behaved himself—at first. He shot hoops with Kellie, taught Jason how to play video games, and wrestled with him on the floor.

Only Tonni sensed that something wasn’t right. “I’m onto you,” she told him. “I’m not as dumb as my mom.” And soon enough, the monster came out.

It started with the shouting. All three siblings struggle to describe the vicious, booming arguments between their mother and Gomes. His voice was plug-your-ears deafening, run-to-your-room terrifying. When he drank, it was worse. Much worse. And he drank a lot. When he was drunk and mad, “he was like the Incredible Hulk coming alive,” says Jason, whose own voice is mildly hypnotic for its slight Southern lilt and gentle tone. Often, Gomes rode the crest of his rage right into Jason’s room. He’d demand the boy stop playing his video game and then pummel him when he didn’t do it fast enough, or send him to the yard to pull every single last weed. “If he couldn’t inflict pain, he would find other ways, emotionally, to destroy you,” says Jason.

Gomes found plenty of ways to shatter Jeanette’s self-esteem. He monitored her calls. Took her paychecks from her teaching and cleaning jobs. Demanded receipts as proof she’d gone where she said she was going. Under the man Kellie once likened to a warden, her fun-loving mother dissolved. “She was sad all the time,” says Kellie. “Some nights he wouldn’t come home or he’d come stumbling in drunk. It would tear her up.”

The wrestling matches got more painful. The choke holds got tighter, the arm behind the back went higher. Jason cried but he never told Gomes to stop. The boy was intent on showing the man how tough he was, how much he could take. His mother stood by, pleading, yelling, powerless.

Gomes gave Tonni a wider berth. He chose instead to mess with her head—standing on the sidelines of her track meets, he’d taunt her about not being good enough.

But for Kellie, it was worse. Far worse. What happened drove her out of the house, to the one place she felt safe, the one place she was free of fear, the one place she could still be the kid from the cul-de-sac, the kid determined to be the fastest one out there.

The track.

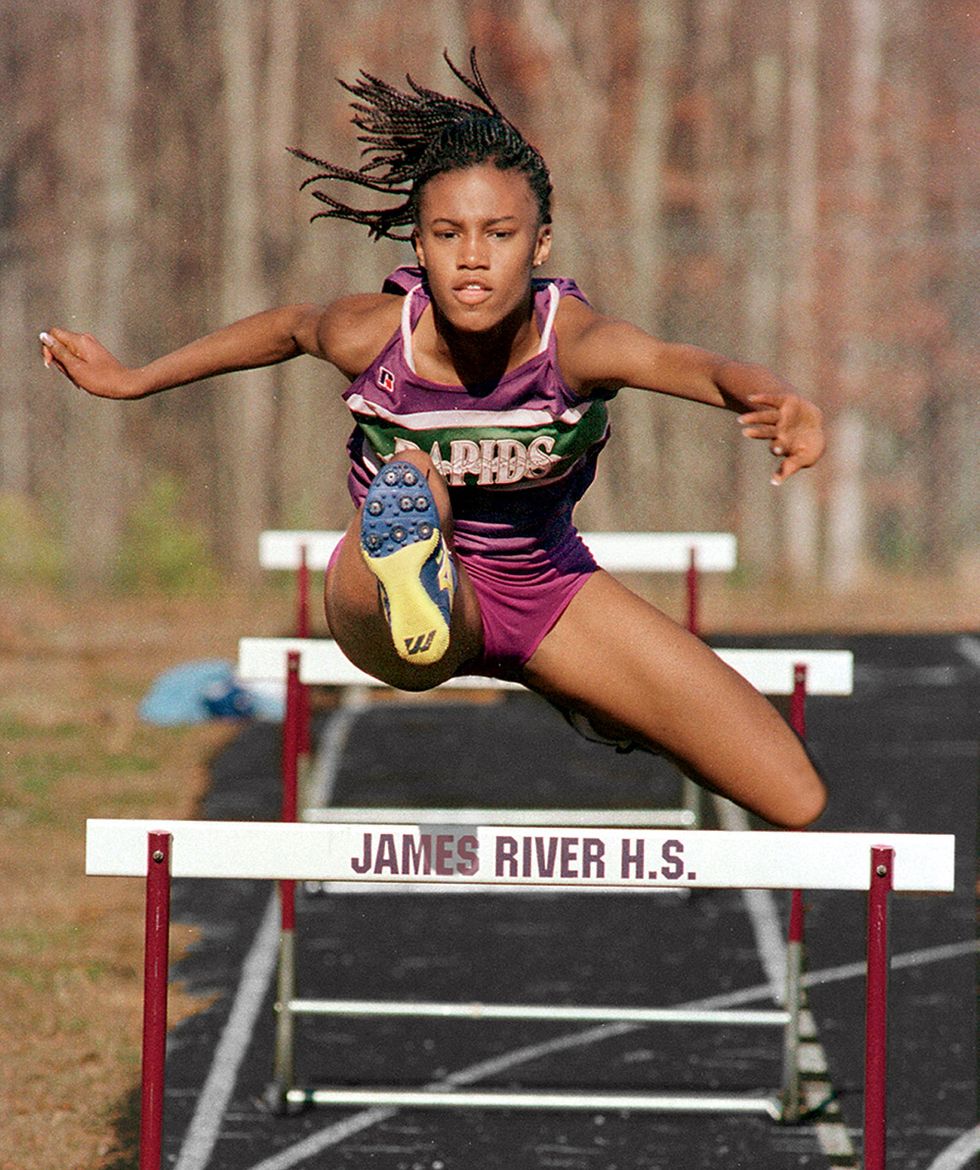

THE BLACK OVAL AT JAMES RIVER HIGH SCHOOL in Midlothian, Virginia, lies nestled between sets of bleachers on a field behind a sprawling tan- and mauve-colored campus. Its surface has aged poorly in spots. The top rubber layer of turn one is broken and pocked from overuse by kids warming up for everything but track—cheerleading, football, lacrosse. The straightaway to turn two is laced with cracks harboring rows of tufted grass.

When life fell apart at home for Kellie Wells, things came together on the track. “Track has been my mate for the longest time,” she says. “I ran when I was upset. It’s always been something I knew how to do well, and when everything was going wrong, track was going right.”

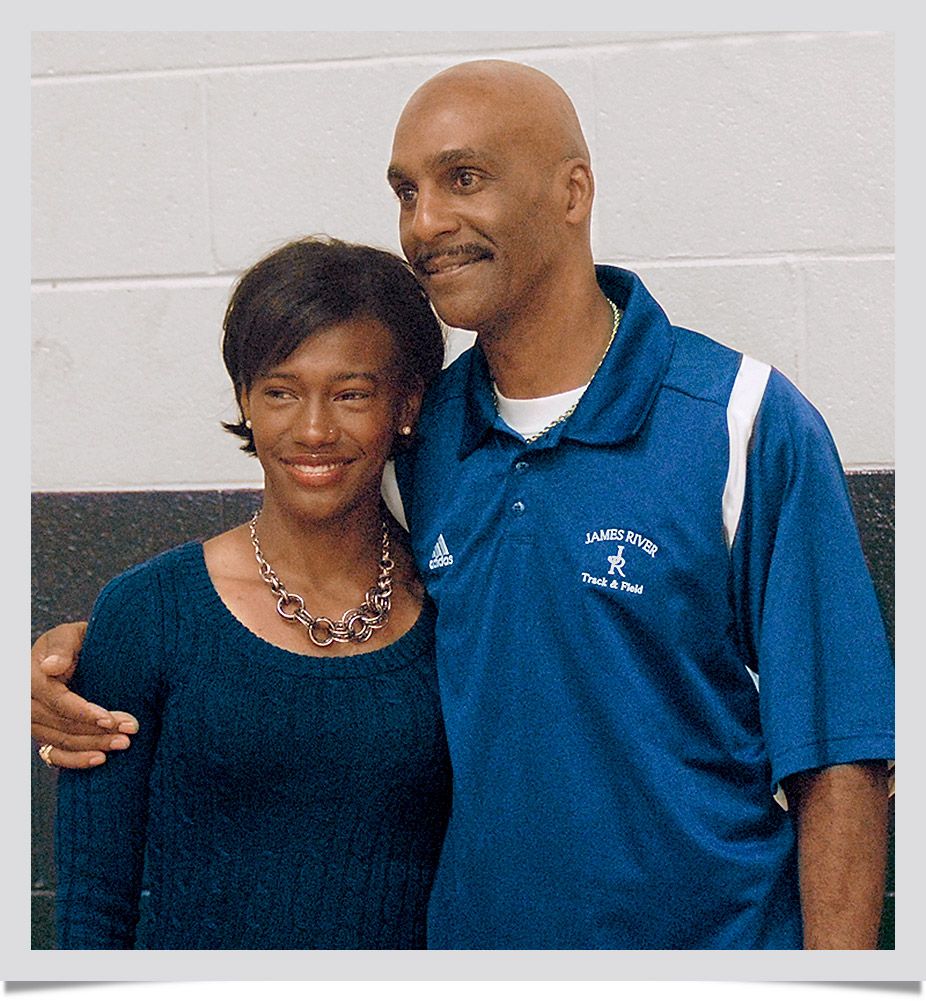

By the time Wells entered high school, she could do—and win—it all: high jump, triple jump, long jump, hurdles, relays. “She was thin as a rail and fast as hell,” says Vatel Dixon, head girls and boys track coach at James River. Dixon, 56, is tall, lean, and bald with a thin black mustache. He speaks in a soothing, melodic drawl that belies a fierce intent to win, and appears to know everyone—teacher, coach, or kid—on campus. He’s been coaching track for 33 years; 2012 will be his last. In all those years, he never had a runner like Kellie Wells.

“That child was just unbelievable,” Dixon says. And infuriating. “She was so talented that she didn’t have to work hard. She’d do what she had to do and win six events, and the numbers she gave me were outstanding, and I’m standing here steaming because I want her to do more.” He shakes his head. “I was always on Kellie. I wouldn’t let her give me less than her best, and she kind of rebelled against that at times.”

Wells brought Dixon’s nascent James River Rapids team “from worst to first.” She was the captain who carried the team—and developed an attitude. She’d come to practice late, or not at all. She could run faster, but wouldn’t. Finally, Dixon drew the line—gifted or not, she would run the program’s way or not at all. He benched her for a meet. The team lost, and Wells was devastated. But that set her straight, and Dixon has told certain runners since then: “I sat my All-American Kellie Wells down. I’ll sit you, too.” Under Dixon, Wells went on to become the first All-American and first state champion in the school’s history.

Though they butted heads, Dixon became a father figure of sorts to Wells. She made him cards, gave him school photos, hung with her co-captain in his office. To this day, she calls him on his birthday and Father’s Day. He keeps an archive of her accomplishments, underlining in red pen or highlighting in yellow portions of newspaper stories detailing her ascent from high school superstar to the fourth-ranked hurdler in the world. It is a time line of pride and love; she was his girl. But until recently, he never knew what happened to Wells when she left his track, or how she was able to put it aside and run like hell.

“Man, that just did it to me,” he says. He stops short and looks off at the track. He had watched over that girl for years; she never dropped a clue, never once reached out to him. When he turns back, his eyes are glistening, and he’s speaking to someone who is not there. “I could have helped you,” he says quietly as the tears begin to fall. He wipes them away with his shirt.

KELLIE WELLS WAS 16 YEARS OLD WHEN RICK RAPED HER. Fixing Dianes Brain.

It started when she was 11. Maybe 12. Ages and dates are fuzzy. But one night, Wells had complained about her back. She’d pulled a muscle playing basketball. She was alone in her room when Gomes came in and shut the door. He had Bengay, or something like that, for the soreness. For a massage. He sat on her bed. He rubbed. And then he touched. And that’s all she will reveal. She was too afraid to move.

The next day, Wells told her mother what had happened. She doesn’t remember much other than her mother’s silence. She does recall that at one point, her mother blamed her for what Gomes did. “She swore that I loved it,” says Wells. “Like I put myself next to him. But I didn’t. I’m a child; I don’t want a man touching on me. She didn’t mean it. She was brainwashed.”

Jeanette confronted Gomes, who denied it. And gradually, the abuse became normal. Night or day, two or three times a week, Gomes would sit too close to Kellie. Force her to cuddle. Rub her chest with Vicks if she got a cold.

One night, Wells felt the covers rip away from her chin. She awoke to find Gomes hovering over her, silhouetted in light from the hallway and reeking of alcohol. He was screaming at her and holding something against her neck. She could feel the edge of a kitchen knife on her skin. She didn’t move. Gomes’s drinking buddy charged into the room and dragged him out before Gomes could go any further, and shut the door behind them. No one came to comfort her.

Such things were impossible for Jeanette to miss, and it seems inconceivable that she would not act. But as the experts will tell you, a victim of domestic violence is not unlike a victim of torture. The level of abuse and control Gomes had over Jeanette made it virtually impossible for her to make the decisions that would have kept her family safe.

Kellie understood that her mother was not keeping her safe. But she loved her mother; they were best friends—they played and sang and danced together. And she saw what Gomes was doing to her mother. He punched and slapped Jeanette. And oh, God, did he yell at her. And so, riding the twisted logic of abused children, Kellie decided it was her job to protect her mother. She was scared and confused, but she wouldn’t tell anyone. Not even Tonni. All Tonni knew when she left for college was that she was plagued with guilt and fear over leaving her siblings behind.

Fear sealed Kellie’s secret, too. Living with Gomes meant she no longer lived in her county school district. He threatened her all the time: If she told anyone about him, he’d tell the school, and she’d end up in the bad, metal-detector city schools. Kellie needed her school. Her friends. The track. Especially the track.

The track couldn’t help her, though, the night Rick raped her. Tonni remembers the frantic phone call a few days later. Both Jeanette and Kellie were on the line. Kellie was crying and blurted out that Gomes had been touching her—the rape itself was too painful to discuss. Tonni started screaming into the phone at her mother. “How are you going to handle this?”

“My mom was so calm. She said, ‘She’s going to live with your father,’” says Tonni. “I was so angry. I said, ‘Will you wake up? Why aren’t you leaving?’ I felt helpless.”

But Gomes had rendered Jeanette nearly incapable of protecting herself or her children. Now, she’d lost Kellie, who moved back in with her father. Despair and sadness manifested into harsh words—for two weeks mother and daughter argued on the phone. At one point, Kellie told Jeanette to wear her seat belt whenever she drove with Gomes; she just had this feeling. Please wear it, Kellie said. Her mother shot back: “You can’t tell me what to do. You don’t live here anymore.”

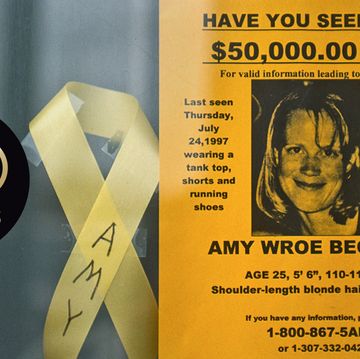

KELLIE WELLS WAS ON HER WAY TO HER DAD’S that night, late for curfew, and getting later by the minute. It was stupid traffic for 10:30 on a Saturday—nearly at a standstill. Wells had been at her dad’s for about two weeks. When she finally made the turn to his condo, Wells looked down the steep hill to her right. A white sports utility vehicle was flipped over on the side of the road. When she walked in the door, her father immediately asked why she was late. She explained that an accident was holding up traffic, then thought nothing more of it and went to bed.

Hours later, her father woke her. He said the vehicle she’d seen was Gomes’s, and that her mother was dead. Had it finally betrayed her? Wells asked him where Gomes was and envisioned going to the hospital and tearing every tube from his body. But he was dead, too.

Coach Dixon couldn’t believe it when Wells and her father walked into his office at 6:45 that Monday morning. He’d heard about the two-car, drunk-driving accident on the news. Wells wasn’t crying, but she wasn’t quite there, either. Her head hurt, and she desperately wanted to be alone. But there she was telling Coach Dixon she planned to run in the meet on Tuesday and Wednesday. Jeanette didn’t like letting people down, and Kellie’s team needed her. It’s what she would have wanted. So Wells ran. For a few hours, the track took her heartbreak away and replaced it with meters and seconds and barriers. Things she could control. Things that gave her peace. She led her team to first, winning six events and setting four meet records.

Kellie, Tonni, and Jason buried their mother the next day.

THEN…LIFE WENT ON. JASON MOVED IN WITH KELLIE AND THEIR FATHER, whose anger was still present but paled next to Gomes’s behavior. And Wells kept running. The fact that she beat a lot of girls much bigger than her attracted Maurice Pierce, head coach of Hampton University’s women’s track-and-field team in Hampton, Virginia. “I was amazed that someone that small could do so many events and be so aggressive,” says Pierce. “You don’t typically find someone that size who can sprint, hurdle, and jump.”

Pierce recruited Wells to Hampton in spring 2001, and they established a rapport almost instantly. Eleven years her senior, Pierce came to regard himself as more brother than coach, and laughs when recalling his Kellie Wells coaching strategy. “I didn’t have to do a whole lot,” he says. “She was fit and ready to run. I just had to keep her sharp.” He knew he was dealing with an uncommonly tough athlete. Mentally, she was a rock. On the track, she didn’t suffer from self-doubt; she didn’t need reassurance during the warmup to a big event. Pierce just left her alone and let her do her thing. Frustration? Disappointment? Not her problems, he said. She was determined to beat the odds.

“She wasn’t coming from the lights-camera-action of a big school, from the happy household,” says Pierce. “She’s a struggler. A survivor. The one who wasn’t supposed to make it.”

Running well at Hampton meant she just might make it—to a pro career, even the Olympics. She buried herself in the possibilities, hitting the gym, tracking her competition, studying the latest workouts and techniques. While her friends and teammates went to house parties on Saturday night, she lay in bed, resting her legs and watching TV. She wasn’t quite an ascetic; she consumed an astonishing array of junk food—Doritos, DoubleStuf Oreos, Honey Buns (a habit she surreptitiously continues today). Holidays, she stayed alone on campus to train. Trips home were brief and unpleasant; her relationship with her father was strained, and remains so to this day. Tonni was in Los Angeles, and Jason was sorting out his own life in Richmond. She was on her own. It was just her and the track.

So her teammates became her family. At mealtime, the track squad had its own table; if you weren’t an athlete, you were a pedestrian, and pedestrians did not sit at the track table. And while Wells was faster and more talented than most of the women, she could rally the others, too. “She gave it everything,” says Arionne Allen, 26, a former 400-meter runner, teammate, and friend of Wells’s at Hampton and now her marketing manager. “She was always in the front. If we were running ladders, during the recovery she’d encourage everybody to give it 100 percent because it’ll pay off. We believed in her.”

At meets, she often competed in up to six events, but instead of chilling out with her feet up between starts, she’d help her teammates bring it home. “In track, you can get lost in your individualism, but Kellie didn’t have that mind-set,” says Nikia Wynn, 28, a former triple jumper and Wells’s best friend in college. “She was always right there at the fence, cheering us on.”

Tight as the team was, it took many months before Wells could talk about her mother’s death, and several years before she revealed some of the abuse. Only Wynn learned the entire story at the time. “Kellie does a good job of masking things,” says Wynn. “Sometimes people do or say things and you think, ‘That’s a sign of abuse.’ I didn’t have any of that. I had no idea. Kellie said, ‘Nobody does.’ Nobody knew.”

They did know that graduation day would be tough. While at Hampton, Wells had garnered three Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference championships, become the university’s second All-American, and led the Pirates to four consecutive indoor and outdoor championships. But graduation fell on Mother’s Day. Jeanette had desperately wanted Kellie to get a college degree. Get a career, not a job. Don’t live like this, working all the time. Inspired and propelled by her mother’s memory, Wells had run fast and studied hard, becoming an Academic All-American. “It was easy for me to get a degree,” she says. “I didn’t have three kids, a man abusing me, and bills to pay. I just had to run track.” Graduation day, families piled out of vehicles and mothers embraced daughters. No one came for Wells. She had gotten used to being without her family, but that day was different. It was too hard not to cry. But when she walked across the stage, the track provided again: Her teammates started shouting, clapping, singing, and throwing confetti, and Kellie Wells was lifted, for a moment, out of her sadness.

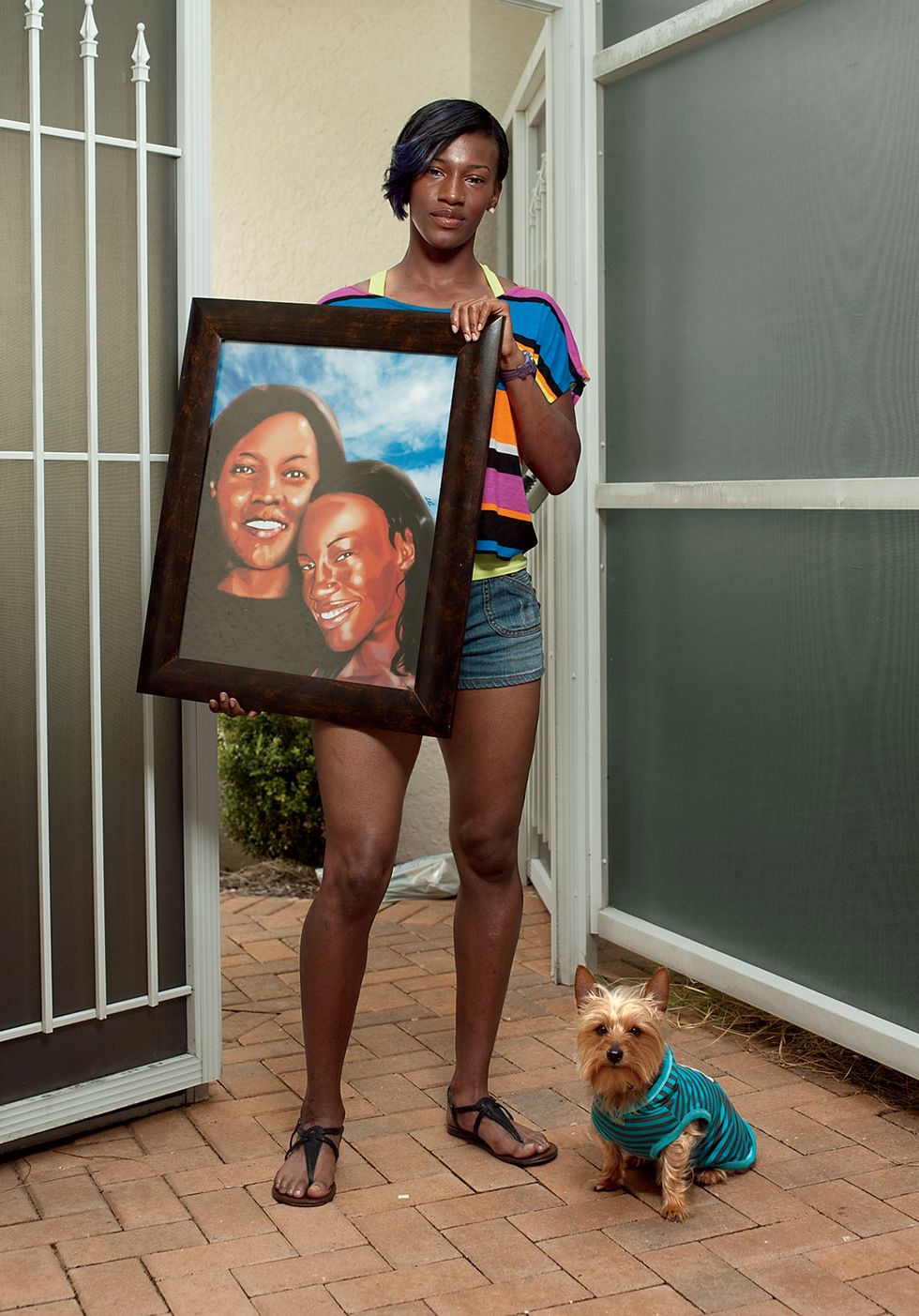

FEBRUARY 2012: IT’S NEARLY 8 BEFORE WELLS HAS A CHANCE TO SIT DOWN. It’s a balmy night in Clermont, Florida. She just moved into this townhouse in a gated community and is living out of boxes. The walls are bare. Boxes marked “kitchen” are stacked at the end of the breakfast bar. A single chandelier, dwarfed by the cathedral ceiling, hangs above a tiny kitchen table. A soft sectional is tucked in the corner, and Wells sits at one end. She’s wearing a green velour tracksuit and no makeup, her black hair pulled into a ponytail that she frequently pulls on. She has high cheekbones and dark, nearly black, almond-shaped eyes. She is frequently distracted by text messages and the 46-inch flat screen, which is nearly always tuned to MTV or a movie channel, and kept on low during the day to keep her Yorkshire terrier, Sebastian, company. She is tired, but unfailingly polite, and despite the competing screens, mostly looks you straight in the eye.

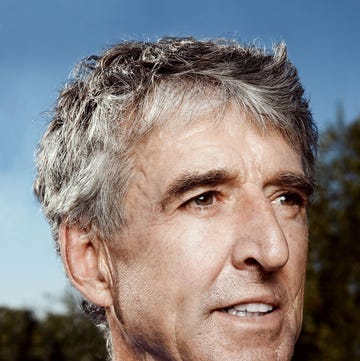

She first set her sights on Clermont as a junior at Hampton. That year, she ran a conference championship in Orlando, where she hit a hurdle and fell. But in the seconds before she went down, something about her caught Dennis Mitchell’s eye. Mitchell, 46, was a world-class sprinter and three-time Olympian who now coaches professional athletes at the National Training Center in Clermont. He was impressed with her spark, her determination. So he found her after the race, and told her to pick her head up. And if she was looking for a place to train after college, she could come to Florida.

After graduating, it took Wells a year to save the $1,700 or so she needed to get to Clermont. In late 2007, she moved to Florida, adopted Sebastian, and began the shoestring existence of an athlete without a contract. From 9 until 2 she trained, and from 3 to 10 she worked one of her two jobs—babysitting on Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday, and training clients Monday, Wednesday, and Friday at the National Training Center’s gym. For eight months straight, she was always tired and almost always broke.

“There was a time when all I ate were potatoes,” she says. “They were cheap, filling—$3 a bag. I had to pay bills, pay Dennis, pay for physio.” She cups six-pound Sebastian’s tiny face in her hand. “He got good dog food, and I got potatoes.”

When Wells started with Mitchell, her personal best in the 100-meter hurdles was 12.93. Her training partner—and Mitchell’s wife—Damu Cherry had a PR of 12.44. That half-second was the difference between good and great. Wells was a lionhearted competitor with lungs of steel, but she was no longer a Big Fish. She lacked strength in her stride, speed to her turnover, and understanding of proper form.

To the casual observer, those three steps between hurdles don’t look complicated. But they must set a hurdler up for a takeoff and landing that propels her forward rather than down—not an easy task when you’re going upward of 17 miles per hour. Being short and not as strong meant Wells’s stride was stunted, so by the time she finished her third step she was taking off too far from the hurdle. As her body traveled the arc to clear the barrier, she would hit the apex of the arc before she was over the hurdle, and essentially “fall” off the hurdle, stalling her momentum. Building her lower body strength would increase her stride length, putting Wells closer to the hurdle so when she took off, she would reach the apex of her arc at the top of the hurdle and come off the hurdle running.

Hurdle form itself is notoriously hard to master—it can take years. Concepts like “the chin dictates the shoulders” and “the pump of your arm dictates the rotation of your trail leg” meant nothing to Wells at first. The what of your what?

It was a steep and structured learning curve. At Hampton, with Pierce, Wells always had some leeway, some say in her training. With Mitchell, there was just one way: his. Deviate from his plan, question his plan, and home you go.

Mitchell sent Wells home a lot. He’d tell her to do something, and she’d fire back with a smart comment or major attitude. It was hard for her to interpret his direction. When it comes to men telling her what to do, instructions for Kellie Wells the athlete always sounded like commands for Kellie Wells the human. “In the beginning,” says Mitchell, “it was like, ‘Anything you tell me to do, I’m going to fight it. Even if I’m wrong.’ Over time, it’s been, ‘Okay, I’ll let you have this one. And this one.’”

Wells knows she’s got a problem with male authority. She’s butted heads with every single one of her coaches, and she’s learned from them that not everyone out in the world is out to get her. But kids who have been abused surrender the luxury of trust. Often for good. So she never lets her guard down; she is leery of everybody. Who knows what their intentions are?

But slowly, Wells let Mitchell have her back. On the track, and in the gym, she hit it hard. She and Cherry started pushing each other so intensely their workouts turned into mini meets. In the spring of 2008, she raced the prestigious Golden League in Europe; with every race, her time fell. She started making money. Quit her jobs. She was fit, fast, and healthy when she lined up for the Olympic Trials semifinal that July afternoon. Not a twinge, tingle, or pinch. Picture of health. Her goal had been to make the finals, but when she won her qualifying round and the quarters, that goal evolved. By the time she hit the finish of the semi behind Cherry, it shifted. I could make the Olympic team.

And then she heard the pop.

Health & Injuries. The second on crutches. By the third or fourth week, she had graduated to one crutch. A month passed before she walked unaided. For a while, she stayed with Mitchell and Cherry, who cooked and cared for her. It was a weird, awkward, emotionally fraught time, with Cherry preparing for the Olympics and Wells too damaged—physically and mentally—to leave the couch.

When she moved back home, she largely lost touch with her track people. She sat alone in her apartment, watching TV with Sebastian. She went to rehab, did some pool work, and tried to walk a little bit. Through occasional tears and a relentless bout of depression, she relived the before and after again and again, saw in her mind the carrot of Beijing so close, and saw it—felt it—rip away again and again. Her aimless days were filled with doubt: Could she get that fit again? Could she afford four more years of training? Did she have the willpower to make all those sacrifices all over again?

Running Shoes & Gear?

As 2009 began, the pain subsided just enough for her to return to the track. But she was unmoored. No longer sure of herself, she lived in fear. What if she hit a hurdle? What if she got hurt again? She had never been afraid on the track. Where had the lion heart gone? She tried to practice, but the pain persisted and the fear stuck and her technique flailed. She could not do her job.

And when she couldn’t do her job, when she was frozen in place with all that energy that used to be channeled over meters and barriers and seconds, her mind started to race.

Mother’s Day was approaching. She knew she would reach out to her friends who are mothers, go to church, pray, and think about the good times. She still cried over her mother, but she was older now, and the pain and sadness had moved to a quieter place. As she sat alone, too hurt to train, she thought about the arc of her life. Her anger and shame had moved to a quieter place, too. Those emotions had buried her secrets for so long, kept her distant from friends, evasive. It was time. She was ready to let those secrets loose.

Wells had a blog—like most professional athletes, much of her life was spent in transit, waiting, or resting, and she kept a blog for something to do in her downtime. It took her three days to wrestle the memories of her childhood out onto the screen. It was exhausting, recalling dates and ages and events. She painted a broad picture of her abuse and left out the rape. When she typed the last period, she hit ‘publish,’ and sat back on the couch, drained. And a little nervous.

Some people read her revelations and thought she’d shared too much. Some of her closest friends were shocked and hurt that she never confided in them. But largely the response was positive, and ripples of support turned to waves of praise for her courage.

She began to think that perhaps her story could change a life.

WELLS DID NOT RACE SERIOUSLY AGAIN UNTIL 2010. That year, she ran a handful of meets, and most were mediocre. But then she proved the doctor wrong and ran fast—she was second at the Outdoor Championships in Des Moines in June.

That fall, Wells sat in a group meeting with Mitchell at the training center in Clermont. They were discussing the coming year. He turned to her and asked, “You healthy?”

“I’m good.”

“You ready to train?”

“Of course.”

“Aren’t you tired of being a lane filler?”

“And I was like, huh?” she says. “He said, ‘Aren’t you tired of being the girl they don’t need in a race, the one they let in because they don’t have enough hurdlers?’”

That comment pulled a trigger. She was going to become the girl those races wanted, the one they needed. From that day on, there would be no more mediocre days. If she only had 50 percent to give, she’d give 100 percent of that 50. “It was pedal to the floor,” she says. Off the track, she researched nutrition and borrowed moves from other sports to build a stronger core. She scrutinized endless YouTube videos of the once dominant and eerily calm East German hurdlers. She reviewed her past races, identified her mistakes, and used her practices to erase them.

In 2011, she went undefeated through the indoor season (the indoor event is 60 meters long with five hurdles). She destroyed the field at Indoor Nationals in Albuquerque in February, running the third fastest indoor time by an American, behind Gail Devers and Lolo Jones. The spring outdoor season progressed on a mixed note as she continued to hone her technique. And then Sunday, June 26, rolled around. It was Outdoor Nationals in Eugene, Oregon, on Hayward Field. The track that nearly broke her heart.

Soon after arriving, she went to the track, walked to lane four, and sat down. She patted it. Talked to it. I am not afraid.

Shortly after 2:30 p.m. on a sunny, Sunday afternoon, the gun went off. With each hurdle Wells attacked, she gained on the field, and when she broke the tape, there was daylight before second place. Her time of 12.50 was the world’s fastest to date for 2011. As the tape fluttered to the ground, she began to shriek with joy and relief and gratitude. She fell to the track, rolled to her back, sprung up, pumped her arms, dropped to her knees, put her forehead on her hands and wept into the track. She had made her first team; she was going to the World Championships in Daegu, South Korea.

KELLIE WELLS WAS 16 YEARS OLD WHEN RICK RAPED HER.

Her comeback wasn’t enough to crack the general public’s indifference to track and field. But it attracted the media. When Wells exposed her past—all of it—to a Yahoo sports reporter who’d read her blog, her story went beyond track insiders and became the story of abused children and families all over the country.

She was inundated with requests to speak—to girls’ groups, middle schools, high schools. In person, over email, on Skype. She accepts all she can, tailoring her message about working hard, making choices, and finding good people to latch onto. She encourages the kids to friend her on Facebook and follow her on Twitter, and she tries to write every single one of them back.

“If I can help just one person, it will make my life worthwhile,” Wells says. “I don’t want young girls to go through what I did. I found a good path and had good people to guide me. Not everybody is that lucky.”

The idea she’d had after writing her blog has hatched into a movement. She and a core group of supporters are devising plans for a foundation in Clermont to help victims of domestic violence and sexual abuse. The foundation will provide placement homes because that’s what Wells and her family needed—someplace to go. And it will offer counseling because that’s what her mother needed—someone to talk to about a love that felt to Wells more like an addiction.

IT’S LATE FEBRUARY AND THE WIND IS BLOWING strong across the bright orange track at the National Training Center in Clermont. Hard enough that a sprinter doing long repeats wants to finish those repeats with the wind at her back. Wells crouches at the 100-meter mark and springs forward on her own signal. She’s wearing black capri tights, a black long-sleeve sports top, and a black brace on her right arm. She barrels into the wind, knees high, arms pumping furiously. She’s running 250 meters, aiming for “14 or better.”

“Gotta stay on that now!” Mitchell shouts as she whips down the homestretch.

She hits the finish mark with a pained shriek and strips down to a red tank top. “Thirteen high,” Mitchell says, as Wells walks across the infield, her head down.

After the second repeat, she lets out an agonized groan and drops to the track. For a few seconds, she lies on her back, knees up in the air. Then she gets up and disappears into the bathroom off the back straight. She goes into a stall and throws up her toast and coffee. When she emerges, she and Mitchell start arguing about something. “I broke my radius!” she says. “That means there’s nothing wrong with your legs!” he shouts back.

Three weeks earlier, she had been working on acceleration, doing repeats over low, shin-high barriers. She was sailing when she got wrapped up in the second to last hurdle of the final repeat and landed with such force that her right radius—the outer forearm bone that runs from elbow to wrist—snapped. The break required surgery, a plate, and pins, the scar resembled a row of railroad tracks, and the injury ended her indoor season before it began. She wanted to freak out a little. Oh my God, the Olympics. Mitchell will not let her. “We need to focus on the day,” he says. “The things that are at task today.”

It’s been an up-and-down stretch for Wells. In Daegu at the end of August, she was on fire. Flying in practice. She finished second in her semi and made it to the final. When the gun went off, she cleared hurdle one effortlessly, in great position. Hurdle two came up a little fast. By hurdle three, she barely got her leg up in time. The hurdles were closing in on her. Impossible. She hit the fourth and went down.

All hurdlers go down. Even great ones at the top of their game. It was hard, but Wells accepted the setback. Yes, she then broke her arm, but it’s healing well, and she can train. She just bought a house. She has a good car. Good friends. And now, having come clean on her blog and to Yahoo, she seems to have found a purpose outside of running and a sense of peace that previously eluded her.

STAR IN TRAINING Wells signs autographs at a community event in Clermont with training partner and 2008 Olympian Damu Cherry. / Photo Courtesy Kellie Wells

She will look you in the eye, discuss her dark childhood, and answer you as honestly as she’s able. You sense that she is guarded, and not just with you—too many boyfriends have come and gone. That she offers anything at all is remarkable. Her physical achievements are easy to see, but it is what she has accomplished in her own head that is truly exceptional. She can reflect on the pain of her past and recognize the shadows it throws on her today. She knows she cannot outrun all those shadows. She knows she has a lot of processing to do to fully unravel the knot of guilt, anger, and sadness she’s carried all these years. It’s wedged inside her, but has never defined her. She may ask for help one of these days. But in the meantime there is work to do. A schedule to maintain. An Olympic team to make.

Today’s task is hard. It’s her fifth workout after two weeks off, and it’s amazing how fast the body forgets it belongs to an athlete. These lungs certainly aren’t hers.

After her fifth of six efforts, she trudges toward a blue high-jump mat on the infield and lies down. She covers her eyes with her good arm. “Kellie, get your butt walking down to that 150,” says Mitchell. She moans, gets up, and walks glacially across the grass. She stops after a few seconds, squats down, and puts a hand on the ground. Stands up, walks 14 steps, and squats down again. The wind is still blowing pretty good.

Wells makes it to the 150-meter mark, looking like she’d rather sit than run. “Let’s go—one and done!” shouts Mitchell. She straightens, bends, then explodes. She is running at just 70 percent per Mitchell’s instructions—to her it feels like 150 percent; to the uninformed, it looks effortless.

When she finishes, the agony and relief is etched all over her body. She falls to the track. It catches her, like it always does.

Moments after setting a PR in the semifinals, she tore her hamstring.

Story Update · June 30, 2016

Wells made the U.S. Olympic team in 2012, and the 100-meter hurdles final in the London Games was the fastest in Olympics history. Wells ran a PR of 12.48 seconds and won bronze. “It changed my life in the blink of an eye,” says Wells. “It gave me a global platform to share my story.” Life has been good to her off the track, too. In December, she and fiancé Jasper Brinkley, an NFL player, had a baby boy, and the two will marry this summer. “I feel like I’m living a dream,” Wells says. “I have a family, I have my fiancé. Everything is going in the right direction.” The couple will soon launch a foundation with dual purposes: Wells will work with people affected by domestic violence and sexual abuse, and Brinkley will focus on teen pregnancy among at-risk youth. (He had his first child at age 15.) In the meantime, Wells has resumed training. It’ll be tough to crack such a deep field, but she’s got a new outlook. “I’m not trying to fill the void of happiness I was missing in 2012; I have a sense of freedom when I’m running and hurdling now.” Writer Christine Fennessy admired the willingness of the Wells family to share such a difficult story. “They didn’t owe me or Runner’s World anything,” she says. “I’m always amazed when people are willing to be so open. To me, it’s the bravest thing, and it’s a privilege to be trusted with it.” —Nick Weldon

For help in domestic abuse cases, call 1-800-799-7233 or TTY 1-800-787-3224, or visit thehotline.org.