RYAN HALL WILL BE HAPPY WITH SECOND PLACE. In his prayers, he thinks of entering Heaven, and imagines running through the gates as if into a great stadium filled with people raising a joyful noise. He hopes to be just off the shoulder of the leader, but he won’t attempt a late kick. “The goal of my life,” he says, “is just to follow in the footsteps of Jesus as closely as I can.”

At the risk of committing light blasphemy, let it be said the Son of God may want a new pair of shoes. Not only did Hall win the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials, he was the fastest qualifier in American history, taming a tough New York City course in a Trials-record 2:09:02. It was only his second race at the distance; his first was the 2007 Flora London Marathon, where his 2:08:24 was the fastest debut by an American. Returning to London in 2008, he ran 2:06:17, breaking his own record for the fastest marathon ever run by an American-born citizen. Three marathons, three benchmarks. When Ryan Hall toes the starting line in Beijing, he will be operating at a level of possibility not seen since the days of Alberto Salazar.

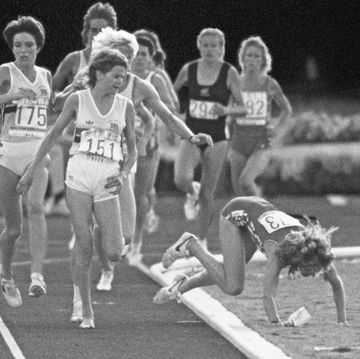

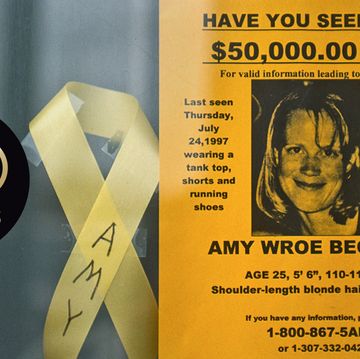

Even so, it’s hard to imagine a race that can supplant the memory of Hall’s win at the Trials. It wasn’t so much the record broken as the galvanizing manner in which he broke it, dusting an all-star pack and covering the final miles less like a marathoner than an amped-up slugger circling the bases after a walk-off homer. But then, in this glorious hour, the darkest news: 20 miles back, his friend and fellow competitor Ryan Shay had fallen dead. Just four months earlier, Hall’s wife, Sara, had served as bridesmaid when their mutual friend Alicia Craig married Shay. All four were record-breaking distance runners with Olympic dreams.

A year has nearly passed, and of the four, only Ryan Hall is set to run beneath the rings. How will he approach the moment? The story will be variously framed: The athlete running for the memory of a fellow racer, the fallen friend, the grieving family; the underperformer who switched genres and scorched his way into history; the man caught in a dialectic in which his most transcendent moment is forever tethered to grim mortality.

Hall prefers another story. The only story, he says; the one that helps us understand why he might remain modest in triumph and strong in tragedy. He calls it the greatest story ever told.

IT’S SUNDAY MORNING, and Ryan Hall is late for church. This is not to imply that Hall is slothful. Quite the opposite. He rose at dawn. For a 15-mile run. Under normal circumstances he knocks that distance down with time to spare before services commence. But this morning he was running in the company of an NBC television crew, and they needed B-roll and interview footage. By the time it was in the can, the Summit Christian Fellowship church choir had taken hymnals in hand. They are currently in full throat, accompanied by electric bass and a drummer on a trap set. The words to the hymns, superimposed over scenes of ocean waves and sunsets, are projected on two pull-down screens flanking the riser. As the verses flip by, the congregation—60 or so people seated in a room decorated with plastic ivy, artificial Christmas trees, and strings of white lights—sings along. As the last hymn prior to worship builds to a crescendo, two men stationed on opposite sides of the room fire handheld confetti cannons. The final notes of praise rise through a powdered rainbow tumbling down.

The church is located across from the Big Bear Disposal Site & Recycling Center. Big Bear Lake, California, is an enclave of the sort and size that operates at the tipping point between the American small town as defined by central casting (old-timers staking out well-worn counter seats at the Teddy Bear Restaurant) and a resort town developed to snag outsiders (Starbucks, faux Alpine lodges, a go-cart course). Set far away from the rest of the world in the San Bernardino Mountains (at roughly the same elevation as that crucible of marathoning, Kenya’s Great Rift Valley), it can be fairly characterized as sleepy on an off-season Sunday morning, and anything but when the ski-booted masses descend at peak time. Today is one of the quiet Sundays. The spring sun has baked a pitchy scent from the needles fallen beneath the tall pines surrounding the church, and the pickups and minivans of the families within sit on the asphalt lot outside. The church building itself is a humble one-story structure painted pale green—you might miss it for what it is should you fail to spot a Calvary’s trio of small crosses planted near the entrance. There is another even smaller cross visible just below the peak of the roof. Before you see either of these, you will probably see the white banner tacked to the siding. In blue letters it reads, “Run, Ryan, Run!”

BIG BEAR LAKE is out there, twinkling in the sun, penned in by a dam on one end, and by mountains to either side. If you drive up from San Bernardino, you’ll want to dose on Dramamine for the switchbacks on Highway 18. The climb terminates in a fork at the dam where Highway 18 splits to run the south shore, Highway 38 the north. Toward the far end of the lake, a bridge called the Stansfield Cutoff reunites the roads, enclosing the water in a 15-mile loop. In a sense that loop is Ryan Hall’s road to Damascus, where the Bible tells us the Christian-killer Saul of Tarsus pulled a spiritual U-turn and became the loyal Apostle Paul. For purposes of conversion, the Lord knocked Saul flat and struck him blind. Happily in Hall’s case, he settled for just tuckering the boy out some.

“In eighth grade I was kind of at a crossroads in my life,” says Hall. You’re about to roll your eyes, looking at this pure-faced blue-eyed 25-year-old with the blond hair, and then he smiles and adds, “I didn’t realize it at the time, you know.” Hall speaks in a southern California patois that, accurately or not, will remind a Midwesterner of surfboards. His sentences are heavily leavened with “like” and he will deploy “gnarly” as an adjective without irony. His gaze is considerate and thoughtful, and apparently incapable of guile. But do not think pushover—he emanates the steadfast resolve of the true believer. If by way of introduction you reveal that you do not believe as he believes, his countenance remains warm and open, but you will catch just a shade of the patient indulgence believers reserve for those yet a-wandering.

“My parents were strong Christians,” he continues. “I definitely believed, but I wasn’t really strongly pursuing my faith. I was playing baseball, basketball, football—I was into, like, the cool crowd at school. And then one day traveling down the mountain to a basketball game, I got this random—I describe it as a vision, but you could call it an idea, whatever—this thing pops into my mind where I am looking out at Big Bear Lake, and I think, well, it would be a great thing for me to try and run around that.”

It’s tough to put this in context now, what with the mind-bending marathon times in the books and Beijing right around the corner. But Hall wants you to understand that the power of the vision lay partially in the fact that he was not being asked to do something to which he seemed naturally inclined. “I never really had any interest in running. Like, in middle school, whenever they made us run the mile, I’d complain just like everyone else. But at that moment it became something that was very captivating…it really grabbed me.”

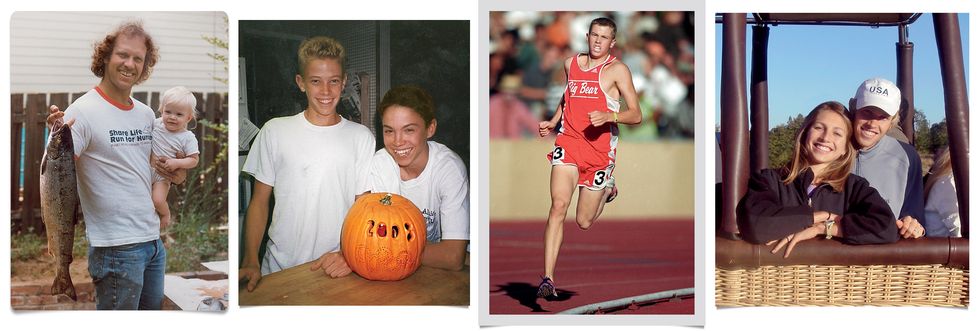

By now, of course, the story about the kid who circumnavigated Big Bear Lake in basketball shoes has become central to the Ryan Hall legend. He ran the route with his father, Mickey. Mickey says they made one stop in 15 miles, and he knew already the boy had something special. The kid was worn out at the end, but back home while unlacing his shoes, Ryan says he too knew this was more than a one-off stunt. “At that point, the trajectory of my life completely changed. All of a sudden I stopped doing baseball, basketball, and football, and started running full time.” And somewhere out on that loop, something else alchemized: “It was at that point that Jesus really became my best friend. That’s when our relationship took off…and it was a direct result of him bringing running into my life.”

At Summit Christian Fellowship, the people are praying. The highest profile congregant has yet to present—he is re-creating that famous day for the cameras—but the flock understands what might be keeping him. After all, they are the ones who hung the banner. They know: God told Ryan to run.

Shoes & Gear regarding athletes who choose to bring their faith to the field reflect the state of our own souls. Fellow believers will likely rejoice at God’s word made manifest in the form of peak performance; nonbelievers will dismiss the testimony at best, deride it at worst. Ryan Hall believes he was chosen by God to run for God. One of Hall’s favorite Bible verses—the one he scribbled on the autographed poster just inside the door of the Teddy Bear Restaurant in Big Bear Lake—is from the book of Isaiah. Those who wait on the Lord, will run and not get tired. The Lord has taught Hall not to overlook that key word: wait. The divine plan doesn’t always run parallel to mortal hopes and dreams.

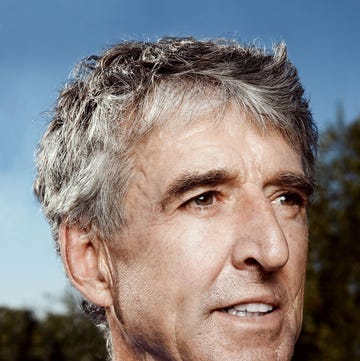

Consider Ryan Hall’s earthly father. Mickey Hall is trim but solid. He is sitting midway up the aisle at Summit Christian Fellowship, and the hand he drapes across his Bible could swing a big hammer easy. In fact, he grew up framing houses for his father. Mickey’s father drove the crew hard. “Head down, butt up!” he would say. “If you’re not in that position, you’re not making money.” By age 42, Mickey’s dad had enough scratch to retire, and “Head down, butt up!” had become the family motto.

If ever a man had the makings of a stage father of the first degree, it would be Mickey Hall. Ultracompetitive (“Maybe what you would call overcompetitive…I wouldn’t let my grandmother beat me in a game of cards!”), drafted as a pitcher by the Baltimore Orioles in his first year of college, and given to obsessive use of a stopwatch (long before he was calling splits for Ryan on the track, Mickey would time the boy and his four siblings as they cut and split firewood), you might anticipate his reaction when he took his son for a run one day and discovered that his progeny was a prodigy.

You’d be wrong. “I tried to convince him to play baseball,” Mickey says, laughing. “He could really throw!” But Ryan wanted to run. So Mickey stopped coaching baseball and started a track program (Big Bear had no track or cross-country team)—and began to deploy that stopwatch the way God intended.

Fraught waters, the whole father-as-coach thing. But Mickey has never forgotten the backstop his father built in the backyard when he was 11. “I would go out and throw half an hour every day at that thing,” says Mickey, and he wound up getting his shot at the bigs. Butt up, head down, yes, but the marvelous thing, Mickey says, is that his dad always assigned work and play equal par. He put down the hammer and took the kids to the beach for volleyball. He taught them to surf and kicked Mickey loose of the construction crew so he could make baseball practice. When Ryan Hall tells the story of the firewood and the stopwatch, the smile on his face tells you the memory is not Dickensian. It is more “can-do” Bobbsey Twins. And it drives him still.

Other Hearst Subscriptions, but that doesn’t mean you’re on the fast track. You’re the man, God told Moses, then sent him off on a four-decade detour. So even in Hall’s immediate and revelatory promise as a runner, his father saw the potential for trouble.

“As a tiny ninth-grader competing against juniors and seniors he ran 4:35 in the mile,” says Mickey. “I never had to push him. If anything, when Susie and I had to discipline him, we’d threaten to take away his training time.” Mickey spent more time riding the brakes than cracking the whip. “I was with him for every workout in high school, and my tendency is to go too hard. So when he would go too hard, I would say, ‘Whoa, we’re done,’ and he’d say, ‘No, Dad, I can do more,’ and I’d say, ‘I know you can—you’re not.’” Mickey Hall’s fastball was clocking 90 miles per hour when his college coach asked him to pitch three innings of a preseason game. At the end of three, the score was tied zero-zero. The coach asked him to pitch one more. Still zero-zero. One more, said the coach. And back in he went, head down, butt up, inning after inning in a meaningless game until the ninth when his shoulder went pop! and the Orioles flew away forever.

Under his father’s guidance, Ryan won four individual state titles in high school and ran a state-record time (4:02) for 1600 meters. The recruiters were circling, and after much prayer, Ryan felt God directing him to Stanford. God also decided it was time to give Ryan a little taste of Job. Before preseason camp even began, he suffered an iliotibial-band injury. “From the moment I started at Stanford, I was off my game,” he says now. “I was struggling with school, I was struggling with my running. I’d wake up in the morning with this heavy burden feeling, like uhhhh, things are not what I had pictured.” He slept poorly, ate poorly, and gained 10 pounds. In the absence of his father’s governing hand and despite the advice of his college coach, he treated recovery runs as one more chance to hammer. Midway through his sophomore year, he was a bona fide flop. He abandoned Stanford for a quarter and returned home. He figured running the familiar roads would help him get things sorted. Help him recover the groove.

It turned out quite the opposite. “I got more depressed. I remember waking up in the morning, trying to go for a run this one day, it was snowing outside, and I just could not get myself out of bed. Went out, and was trying to, like, just do a short, easy run. And I jog, like, half a mile and I start walking. And I just walked home, ‘cause my spirit was just crushed. Because I wasn’t running well, I didn’t see myself as having much worth.”

This time there was no Road to Damascus moment. No blinding revelation. Hall gave himself over to prayer and pondering. “I realized the only things that were going well in college were my relationship with my girlfriend and my relationship with the Lord,” says Hall, who had begun dating champion miler Sara Bei and befriended a circle of like-minded believers through his involvement in the Stanford chapter of Athletes in Action. “I decided that God had called me to go to Stanford.” He returned to the university. “I was no longer a runner who happens to be a Christian,” he says. “I was a Christian who happens to run.”

Things didn’t instantly change. “I still had a subpar track season that year,” says Hall, who cites the end of his 2004 Olympic dreams as a low point. “But I was happy. I knew I was where I was supposed to be, and finally got to a point were I really enjoyed my time up at Stanford.” Before he graduated in 2006, he’d won an NCAA championship at 5000 meters, led Stanford to a team cross-country title, and married Bei. Things were looking up.

TODAY AT SUMMIT CHRISTIAN FELLOWSHIP, the pastor isn’t in the pulpit. He has given the microphone over to his wife and left for the parsonage, where he’s washing lettuce and chopping chicken salad. It is Mother’s Day, and at the end of service, the pastor and several male parishioners will serve a luncheon to honor the mothers in their midst—Ryan Hall’s mother included. The Hall family work ethic and competitive genetics may be patrilineal, but it was Susie who led Mickey Hall—and thus the rest of the Hall family—to Jesus. Mickey was an atheist in flip-flops when he followed Susie to church one day. Took a while, but in the process of writing a college paper about why the Bible was hoo-hah, he wound up a believer. And when Susie began volunteering on behalf of disabled children, Mickey noticed. In fact, when you sort out the chronology, you discover that Mickey turned down cash from the Orioles before his injury. He had seen the joy in Susie’s service, he says, and he was already doubting the little white ball could match that. Now he has been working 21 years as a special-education teacher, and if you want to see his face light up, cut the track talk and ask about those students of his.

Mickey Hall has watched friends thrive in the big leagues. But when he recounts his baseball stories, there is no trace of I coulda been a contender. He revels in the telling. You look at him now worshipping beside the wife who showed him another way, and you see there is no room for regret in the joy. He is fond of quoting 1 Corinthians: “…run the race in such a way that you might win.” Compete with all your heart, he tells his children, Ryan included. “But don’t make it bigger than it is—it’s just a sport.”

A woman makes her way to the front of the church. She has asked that the congregation pray over her. There is trouble on her face, tears coming down. From her modest podium, the pastor’s wife calls on the Lord, and several parishioners close around the woman, some praying with a palm raised to heaven, others laying their hands on the petitioner. Somewhere amid the supplication, Ryan Hall quietly seats himself in the back row.

HALL DOESN’T TAKE MISSING CHURCH LIGHTLY, but with his training and travel, absenteeism has become an occupational hazard. This has led him to examine the life of Brother Lawrence, a 17th century Carmelite monk who taught that Godly people should weave worship into work. “Brother Lawrence was one of the guys who pioneered that thought about doing every single little thing for the Lord and staying connected with him throughout the day in prayer,” says Hall, who often listens to an audio version of the Bible while driving, or on his iPod while running. “Rather than study the Bible at some appointed hour, I try to make worship much more just a natural flow and part of my day,” he says. “A big challenge for me is to pray without ceasing as the Bible tells us. So I pray when I am out running. Or doing dishes. When my mind is wandering, I try and hone it back into praying. I’m not very good at it yet.”

Brother Lawrence also preached Christ-like humility and warned of the consequences of pride. How does Hall reconcile these lessons when his job requires crushing the competition? “There’s obviously a gray area,” he says. “You gotta have confidence. The question is, what are you putting your confidence in: your own ability? And what do you believe about your ability? Do you believe you’ve done something to deserve it? Or is it a gift? I believe I have a gift from God. But then I also have to train really, really hard. So I see it as being a good steward of the gift God’s given me…it’s my obligation to God to develop this talent the best I can. So, I try and make that my focus rather than wanting to beat people. Not that it’s not fun to win, because it is?

“I think part of it too is just being content with whatever the Lord has for my life.”

But whither motivation? If all outcomes—win, place, or no-show—are God’s will, does Hall have permission to lose? “I don’t know,” says Hall, after some thought. “I don’t have all my theology figured out. I don’t know if God has someone in mind to win the Olympic Marathon either. Only one guy can win that race, and everyone in that race wants to win and it’s their dream to win, so what does that mean for the rest of us who don’t win? The 99.9 percent of us who will never get a gold medal in the Olympics? Does that mean that we’re all failures, and that all the training we did our whole life building up to it was a waste? Definitely not.”

In the course of her homily, the pastor’s wife reveals that she will be traveling to Beijing to see Ryan run. She does not want to go to China, she says. She has been telling the Lord so. But the Lord does everything for a purpose, she says, and somewhere in China that purpose will be revealed. Hall listens impassively but attentively. Wearing khaki cargo shorts and an Asics T-shirt, he looks preternaturally fine-tuned, the way all athletes do when at rest among the shlubby rest of us. Every move is a gesture of economy. His hand rests on his Bible, and his Bible rests across his right thigh. There is no dust on Ryan Hall’s Bible. It is hardly tattered, but the gilding on the pages is scored and worn. When he opens it to follow the sermon, it falls open easily to reveal well-thumbed page corners and verses underlined in pen. This Bible is not a prop. You can see him turning to it again and again. When racing for Heaven, one must train to the finish.

“I don’t think I have an exact point in my life when I accepted Christ,” says Hall. “I can remember doing it—you know, as a kid—over and over again ’cause I was kind of afraid the first time didn’t count or whatever. I wanted to make sure I was covered. What I have learned as I have gotten older is that it’s such a daily thing. It’s not a one-time decision and that seals the deal. It says in the Bible to work out your salvation daily with fear and trembling…it’s a long journey and it’s not like you instantly get to this holy status. I am very much still in process, as I think all Christians are. All people are, really…we’re all still growing.”

BIG BEAR LAKE, everyone makes their way across the church parking lot to the parsonage, where tables have been set beneath the shade of the pine trees. Ryan sits next to his father, and the resemblance is strongest when the two men smile in unison. Their upper lips peel back to reveal a generous set of incisors, and you think of Gary Busey minus all the crazy.

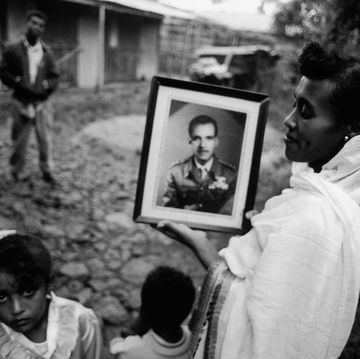

Big Bear Lake has always turned out for ball games, not for track meets. In fact, when Hall won his state cross-country titles, he wasn’t eligible for a letter because there was no team. Nowadays the posters all around town say, “Run, Ryan, Run!” but when he began, the sight of a teen pounding out miles was unusual enough that some lowered their car windows to holler, “Run, Forrest, Run!” When Hall and his parents relate these stories, amusement trumps animus. “There just weren’t funds for a track team,” says Mickey. “Besides, he was getting to do everything we wanted him to do without being on a team.” Now, thanks to Ryan’s high profile and the efforts of a local reporter who raced for Mickey in high school, Big Bear Lake has both track and cross-country teams, and Ryan has lent his support to the Lighthouse Project—a local organization dedicated to creating “child-honoring communities.” Further afield, Ryan and Sara are members of Team World Vision, a charity designed to promote self-sustaining communities in Africa. The couple speak eagerly of the time when they will be able to serve as missionaries in Africa.

As Hall eats chicken salad with a plastic fork, fellow church members stop by to say hello. They call him “Ry,” and happily tell visitors stories about the little boy they knew. The fellow across the table couldn’t give two hoots about Beijing and keeps steering the conversation back to trout fishing and his half-wolf dog.

The utter lack of obsequiousness is a reminder that the Lord need not rain down disappointing splits and shinsplints to keep his servants humble. His touch can be ineffably deft. A man who has been studying Hall from a distance leans to his wife’s ear and asks a question. “Yes!” she says, brightly. “He’s going to the Olympics!” He leans to her ear again. “No, no,” she says, still beaming. “In cross-country!”

YOU CAN ASK A MAN QUESTIONS. You can observe him about his daily business. You can even sit beside him in church. But in your heart you know it’s presumptive to think your brief window can illuminate his soul. It is likewise tempting to posit a natural connection between spirituality and long-distance running. Even at the basest amateur level, running is predicated on periods of extended isolation, meditative rhythm, and regular access to the deoxygenated edge of failure (where the best revelations reside). Hall has been quoted saying that he saw the scarred body of Christ during the last two miles of the 2007 London Marathon. And yet, one shouldn’t get carried away. When he speaks of his faith in his laid-back California accent, it’s unlikely he’ll knock you off your seat. Hall is neither fiery nor overly eloquent in defense of his faith. Remember his words to describe the moment God spoke to him at Big Bear Lake? “I describe it as a vision, but you could call it an idea, whatever…” Disarming but not disarmed, he acknowledges skepticism even as he remains resolute in faith.

“It’s not my goal to convert anyone, you know,” he says in a conversation at the Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista. “I think Jesus invited people to hear what he had to say. I think he told people what was in his heart. I want to be authentic with people…for me not to share why I run or what gets me through hard moments in races would be cheating them. But I’m not going to force someone to hear something they’re not interested in hearing.”

“Do the work, Ryan. Leave the rest to God.” Over and over his father has told him this, but he would dearly love to win in Beijing. He is not impervious. After losing to Alan Webb in the mile at the 2001 Arcadia Invitational, he flung his shoes and went for a long run barefoot. After the Pac-10 Cross-Country Championships in Arizona, Mickey and Susie found him weeping in the bushes. Last year, prior to the Trials, he told his mother he had promised God he would have a better attitude whenever he didn’t do well. “I told him, ‘Expect to be tested on that,’” says Susie Hall, eyes twinkling. “And then he had three bad races leading up to the Trials. He needed to be humbled. People relate far more to the disappointment than the celebration.” (True enough, but oh, that finish at the Trials.)

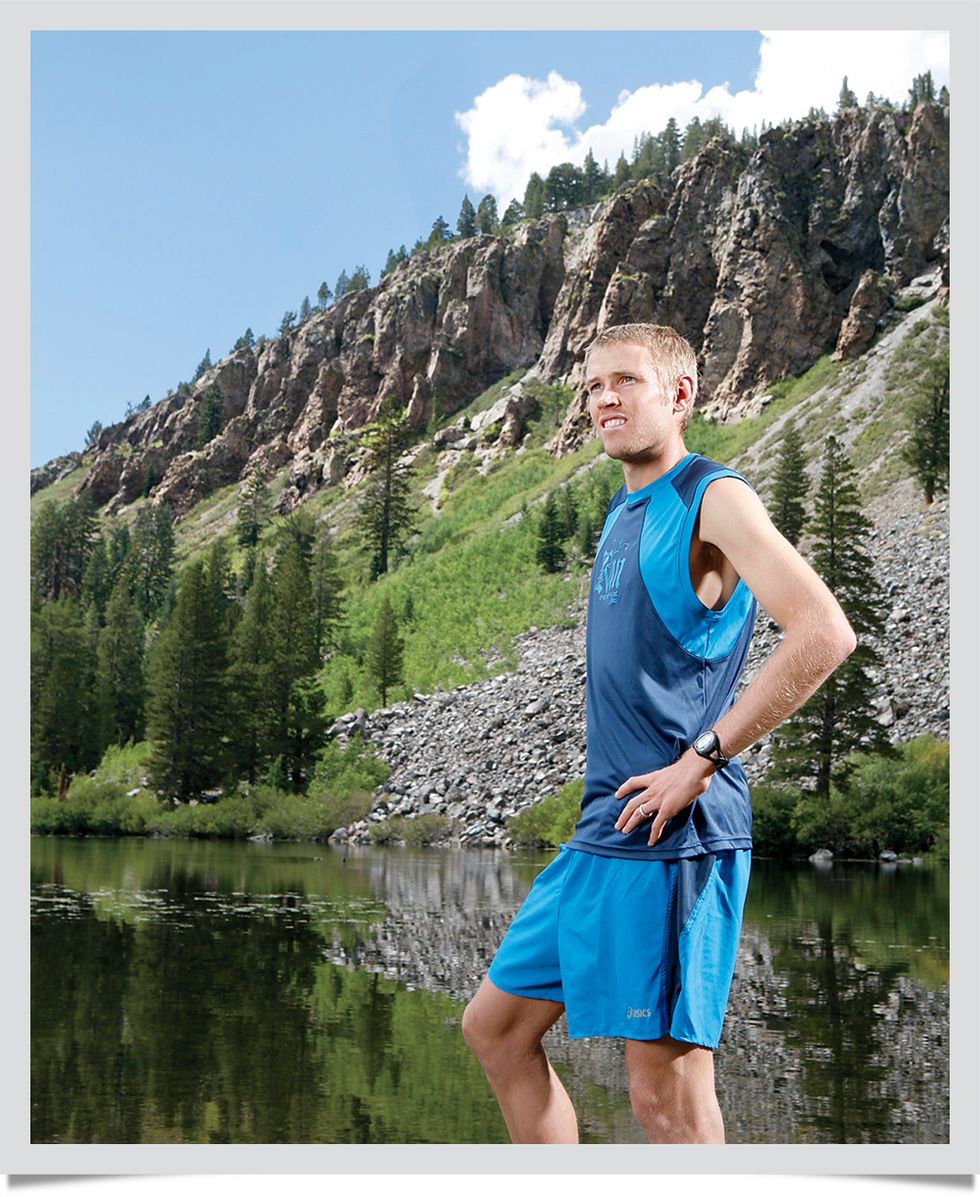

The day before we attended church in Big Bear Lake, I accompanied Hall on a pair of recovery runs at the Olympic Training Center. To keep things fair, I rode a bicycle lent to me by 5000-meter specialist Ian Dobson. Terrified I would veer in too close and be forever known as the man who ruptured the Achilles of the most promising U.S. marathoner in two decades, I followed at a safe distance, which is to say I watched Hall run from a perspective shared by 99 percent of his recent competitors. I was struck by the immaculate nature of his footfalls. Each heel came to earth perfectly square, with no hint of pronation. “His stride was gorgeous from the beginning,” says Mickey Hall. “His legs would just flow.” His torso, on the other hand, is held parsimoniously erect as if to provide the heart and lungs a stable work environment. The stiffness continues in the specific alignment of his thumbs, pointed forward from atop his fists. His elbows are held at right angles and sweep back and forth just above the iliac crest, crossing at the same plane every time. His left elbow wings out a tad—a teensy imperfection held over from an early habit of crossing his body with his arms. Mickey spotted this early and mostly cured it by tying Ryan’s elbow to his side.

But Mickey is right: Everything is extraneous to those legs. You can see them in footage from the homestretch of the Trials, turning over in a pinwheeling lope, each foot meeting the earth right on axis, then looping up and away to fly forward again. The legs are all business right to the finish, even as the arms begin to loosen, even as Hall’s head begins to swivel to acknowledge the noise of the crowd. The closer he draws to the line, the more evident it is that this is a finish for the ages. Hall begins to gesticulate, pointing to the sky, raising his arms high, even slapping hands with the people crowding the course. At first it seems uncharacteristic based on what you know of Hall and his mellow Christian demeanor. Then you notice the blazing intensity of his eyes and the inclusiveness of his open arms, and you realize he is not exulting, but exhorting. He is not celebrating triumph over man but rather triumph in the Lord—in short, this is a man in rapture. Hall often refers to running in terms of sanctuary, and here he is now, Brother Lawrence in a singlet, twining work to worship, running 4:55 splits, praising God full tilt right until he breaks across the line and the only thing left to do is bow quietly down, the work all done, the victory won.

Nick Laham/Getty Images a long day for the Hall family. After the church luncheon, the television crew and I return to their house for a final round of interviews. Susie spreads photo albums on the kitchen table (should you ever qualify for the Olympics, know that the picture of you wearing an Olympics sweatshirt, a diaper, and your sister’s tap shoes will wind up on TV) and serves fresh-baked apple muffins as she runs around the house gathering mementos from Ryan’s career. She has to dig around some. “We don’t keep a shrine to Ryan,” says Susie. “We have five children. We could fill the walls with his things, but we try to celebrate the gifts each of them have.” Ryan and Mickey sit down together and talk for the cameras some, then do a father-son run for yet more B-roll. Finally Ryan—who has learned the lesson of rest and follows a strict regimen of icing, recovery, and massage—leaves for an appointment with his masseuse.

So now the final piece of gear is packed as sunlight slides through the pine trees at a flattening slant. In the living room, Mickey Hall cues up footage of Ryan’s triumphant finish in the Trials. Susie and Ryan’s grandmother Madeline join them, and for a while everyone just watches, eyes raised to the screen. Eventually, Susie speaks. “You know, for three days before every one of Ryan’s races, Mickey fasts and prays. He prays that it will be a good race and a safe race.” Up on the screen Ryan is surging for the finish, strong as a bolting deer, glorifying the Lord with each step. You think of Mickey, on his knees and hungry (so weak one time he fell and wound up in the ER), beseeching that same Lord that He might deliver every runner safe to the finish line. And yet we know full well watching the footage now, that even as Ryan Hall was pointing to the sky and the crowd was making a crazy joyful noise, his friend Ryan Shay was dead. The following night Mickey dined with Shay’s father-in-law. “What do you say to someone who’s lost their son?” he says, shaking his head. “What do you say?” The questions are not new, and hang in the air. God’s mystery will be revealed, answer the believers; grim coincidence, say the nonbelievers.

Hall has at times gone out of his way to play down attempts by outsiders to over-personalize the tragedy by casting him and Shay as best friends, but in the month following the Trials, he and Sara quietly moved in with Alicia in Flagstaff, and Hall will tell you that he trains for the Olympics with Shay’s memory a constant companion. It would be easy to nudge the narrative toward that end. To set the possibility of Ryan Hall ascending the center dais as Ryan Shay’s spirit made visible. It could happen, and Hall will be thrilled if he runs to victory. But he knows first and foremost he must run to honor the Lord.

Ryan Hall’s grandmother is suddenly at my elbow. Her face is troubled. All day she has been a sparkling presence. A petite woman with glittering eyes, her family loves to tease her for her vociferous cheering at Ryan’s races. In private company she is quick to laugh and often punctuates her asides with a knowing grin. But now the house is quiet—Mickey has his son paused up there on the screen—and the glitter in her eyes has gone wet.

“I want you to know…” says Madeline, faltering. “I want you to know that this family prays, and prays for many things. That it will be a good race, that it will be a safe race, but they never…they never…” She stops now, holding her hand to her mouth as her eyes fill with tears. It takes her a moment to gather before she can speak again.

“They never pray to win.”

Story Update · July 28, 2016

Ryan Hall announced his retirement from professional running at the age of 33 in January. The news shocked many—as did his physical transformation over the next several months as he bulked up through weightlifting and gained nearly 40 pounds. The decision came after several injury-plagued years that saw Hall drop out of a number of major marathons. It marked a bittersweet conclusion to what was one of the most illustrious careers in the sport: Hall finished 10th at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, ran a streak of top performances at the Boston Marathon, and in 2011, finished fourth at Boston with a 2:04:58, the fastest marathon ever by an American. He had stints with high-profile coaches Renato Canova and Jack Daniels interspersed with periods of what he described as “faith-based” self-coaching. Hall’s post-running life continues to revolve around his Christian faith. “Every decision I make in my life is made through the lens of my faith,” Hall says. “My faith enabled me to take an honest look at how my body was doing over the last four years, and make the right decision [about retirement] based on my body’s feedback.” Faith also guided his decision to become a father; last year he and his wife, Sara, adopted four Ethiopian sisters. “God filled my heart with love for them,” he says. He’s not done running, either. In January, Hall will attempt to finish seven marathons on seven continents in seven days with his friend Matthew Barnett, a pastor from Los Angeles who is raising money for his church, the Dream Center. “He’s living out his faith and I can admire that,” says writer Michael Perry. “It seems like he’s committed his life to doing good. Who can argue with that?” –Nick Weldon