ON A MUGGY MORNING IN OCTOBER 2003, Julius Achon rose early for a 10-mile run through the streets of Lira, a dusty but populous town in northern Uganda. A former George Mason University track star, Achon had returned to Lira for a brief family visit while training for his third Olympics, and his route that morning was a fast, rough circuit that wound past rural shanties before looping back to finish at the town’s open-air bus depot.

Eighteen years into a bloody civil war, much of northern Uganda had been ravaged by fighting, and the station was almost deserted when Achon arrived, shortly after dawn. Pausing to stretch, Achon glimpsed what appeared to be the bodies of nearly a dozen children lying sprawled under one of the buses, all of them raggedly clothed and covered in dust. Thinking he had stumbled on corpses, Achon backed away. Then one of the bodies got up.

It was a girl, filthy and barefoot. Approaching Achon, she kneeled to beg for money. Reeling, Achon pointed to his singlet and shorts. “I’m running,” he told her. “I have no money.”

The exchange woke the other children. “What are you doing here?” Achon asked. “Our parents have been shot dead,” they replied. Homeless for the past year, the orphans had banded together, begging by day, sleeping by night on the concrete verandas of local shops. Eventually, they had moved to the bus depot to shelter at night under one of the parked buses, where the faint, leftover heat from the engine kept them warm. On impulse, Achon led the children to his father’s home, a straw-roofed hut on the outskirts of town, where he arranged for one of his aunts to make them lunch. Achon watched the children take turns eating rice with beans and porridge from the hut’s few bowls. Most of them were still terribly young. One of the eldest, a rail-thin boy named Samuel, was 10, while the youngest was a boy around 3, who didn’t know his own name. Some were also unwell. Reluctant to return the orphans to the street, Achon asked his father whether they could stay. It was a provocative request. Living space was already tight—eight relatives slept in the nine-foot-wide hut—and food scarce; there was barely enough to feed the family, let alone 11 additional children.

After some discussion, Achon’s father agreed to shelter the children, provided Julius would send money to cover the cost of food. He promised that he would, and the next day flew back to Portugal, where he lived and trained at the time. On the flight, he began to worry. Since leaving George Mason, Achon had signed a contract with a Portuguese running club, which paid him just $5,000 a year, plus a portion of Achon’s race winnings, which had remained paltry. Feeding the orphans would cost Achon roughly $1,200 a year—almost a quarter of his current salary. And while Achon had managed to send money home to his family each month since leaving for college, it had often been a strain. For the past two years, Achon himself had been essentially homeless. Too broke to afford rent, he had slept on a cot in the running club’s basement, a concrete storage area that had no electricity or heat.

By the time he landed, Achon could only hope that he had done the right thing after all.

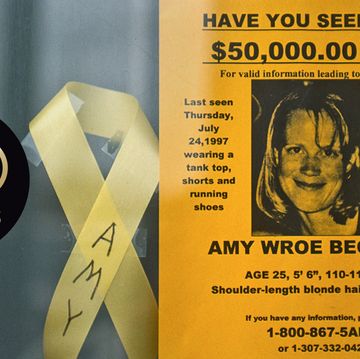

OUT OF AFRICA is John Akii-Bua, a 400-meter hurdler who won a gold medal in the 1972 Olympics. As a boy, Julius Achon grew up hearing stories about Akii-Bua: a legendary figure reputed to own a luxurious car with a custom license plate framed by blinking lights. To Achon, whose own home was a mud hut with a leaky straw roof, shared with eight siblings, such extravagance was tantalizing—so much so that at age 10 Achon began to run, padding barefoot up and down the narrow dirt road that led to his village. At the time, Uganda was engaged in a brutal civil war with the Lord’s Resistance Army, a rebel group notorious for kidnapping children and forcing them to fight. When Achon was 12, soldiers abducted him from a clearing near his parent’s home, which was then in Awake, and marched him to an LRA camp a hundred miles away. Though Achon managed to escape three months later by fleeing into the bush during an air raid, nine other boys escaping with him were shot and killed.

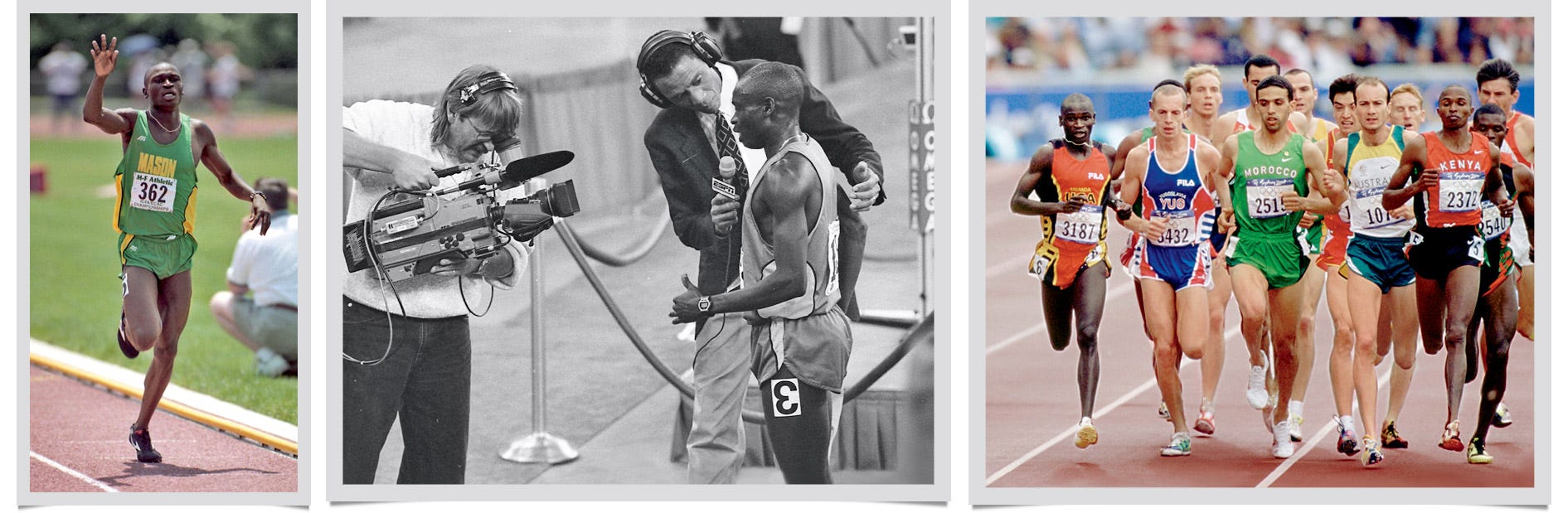

A year after making his way home, Achon entered his first official footrace, a county meet that he won. The race qualified him for the district championships in Lira, 42 miles away, but the county had no money to pay for transportation. When he got the news, Achon took one of the family’s chickens to the home of a wealthy man who owned a car, and begged for a ride. The man refused. Incensed, Achon ditched the chicken and started running. He reached the stadium in Lira six hours later. The next day, Achon ran the 800 meters, which he won, and the 1500 meters, which he won in the final sprint. After a lunch of sugarcane, he raced the 3,000 meters, and won easily.

The victories earned Achon, then 13, a berth at the national championships. They also caught the attention of Christopher Banage Mugisha, the sports master at an elite government-aided high school in the country’s capital, Kampala. When I spoke with Mugisha last spring, he remembered watching the races start, and seeing “this boy with no shoes, running very fast.” Though Achon was barefoot and lacked form, Mugisha recalled, he had speed and grit: “I said to myself, ‘I want that boy.’”

The championships in Kampala began two weeks later. With no time for heats, organizers made the 1500-meter race a mass start. Wary of being blocked by the crowd, Achon followed Mugisha’s advice and elbowed his way to the front, then shot off the line like a hare. The race remained close until the last hundred meters, when Achon dropped the pack on a sprint, winning the race in 4:09.52. As a prize, he was awarded a jerry-can, a five-gallon plastic jug for hauling water.

The race changed Achon’s life. Growing up, Achon typically ate one meal a day and drank water from a local swamp shared by cattle. Because his parents were too poor to pay the annual $15 tuition required for primary school, Achon would sometimes attend on the sly, sneaking into one of the packed classrooms, and escaping out a window when the headmaster came.

Mugisha offered Achon a scholarship at the high school in Kampala. Though Achon was never more than a mediocre student, under Mugisha’s tutelage he blossomed into an extraordinary runner. At the World Junior Championships in 1994, he became the first Ugandan runner to win a gold medal, racing 1500 meters in an astonishing 3:39.78—a 12-second PR. Within days of the race, almost two dozen American colleges had written to offer Achon a scholarship. He chose George Mason University, whose track team at the time was coached by John Cook. Temperamental and eccentric, Cook had assembled what he called ‘a United Nations kind of team’: a cherry-picked roster of international talent. Achon, dedicated and extroverted, soon became one of the stars. The team won the NCAA Indoor Championship in 1996. The same year Achon ran a record 1:44.55 in the 800 meters—a collegiate record that still stands. A few months later, he competed for Uganda at his first Olympics, in Atlanta, in the 1500, not making it out of preliminary rounds.

In the movie version of Julius Achon’s life, this is where the film would end: a fade-out on our hero as he crosses the finish line. It’s worth remembering this moment, the culmination of so much luck and ambition, because as we go now to meet Achon, it’s natural to imagine that his star would continue to rise. In fact, Achon’s tale turns out to be both sweeter and sadder than miles logged and races won. So trust me, dear reader, when I tell you that Achon’s story has only just begun.

Story Update August 11, 2016 at a hotel in Kampala, Uganda. Now 35, Achon still has the compact body of a professional runner. At 5'7", he is slight but muscular, with short-cropped hair and cheeks lightly scarred with matching sets of horizontal lines: clan marks made when he was an infant.

On this trip, Achon was accompanied by a man named Jim Fee, who had until 2008 worked as an executive in the medical-device industry in Portland, Oregon. Fee met Achon in 2007, while Achon was working as an assistant to coach Alberto Salazar, and has since become the unpaid business advisor to Achon’s one-man foundation.

Though the official purpose of the trip to Lira was work—Achon is currently building a medical clinic near his home village and wanted to oversee some of the construction—that morning had the feel of a victory lap. With the help of Achon’s brother, Jimmy, the orphans had spent the past seven years living in a three-room house near Lira that Julius had had constructed in 2004 and eating two meals a day. All were enrolled in school, and Samuel, the rail-thin 10-year-old, now 17, had followed in Achon’s footsteps and earned a track scholarship to a prestigious high school in Kampala, where he hoped to post times that would catch the eye of athletic recruiters from the United States.

In person, Achon is personable and wry, with a self-deprecating sense of humor. Over breakfast, he recalled how, as a young student at George Mason, his naive observations—he initially called snow “white rice”—entertained his teammates. Despite having spent the past eight years living in Portland, he remains ebullient about the small joys of first-world living. “Having tea in the house! Having bread in the house!” he exclaimed at one point. “If I want tea—anytime!—I can have it.”

Recalling his decision to shelter the orphans, he was pragmatic. In Uganda, he observed dryly, housing standards were not the same as in the United States—or as he put it: “If you are poor in Uganda, you just sleep on the ground like the cows.” Childcare was also no problem, since children contributed to household chores and tended to be well-behaved. “As long as there is enough food, they are easy to mind,” he said. And while accepting responsibility had been daunting, he admitted, his time in the United States and Portugal had cast the financial obligation in sharp relief. “I calculated: If these 11 kids stay, for $100 a month I could feed all of them,” he said with a shrug. “When I realized that, there was no other decision.”

Driving to meet the orphans later that day, I repeated this explanation to Jim Fee, who laughed. “When all this started, I asked my wife: ’Can you imagine what it would be like if I brought home 11 kids from the Portland bus station?’”

At the compound, Jimmy’s wife, Florence, was cooking lunch for 25 on a traditional outdoor stove: a clay mound into which sticks are fed to make coals. “This is today’s heavy meal,” Achon said, pointing to two large pots of corn masa and beans. The children get meat twice a week—a major nutritional advantage. When he was growing up in the village, Achon recalled, meat was eaten only once or twice a year, on holidays and at major events like weddings. Since the arrival of the original 11 orphans in 2003, Achon said, the home where the orphans live has expanded; it now houses 15 children, and provides food for up to a dozen more. Conditions have also improved. In 2005, Achon paid $500 to have a private pump installed to supply the house with water, and in 2009, he paid an additional $300 for an electricity pole to give the house light.

Though Achon has described this as the wealthy part of Lira, the place still looks relentlessly poor. The road, which was last paved in 1972, has eroded to a thin, potholed strip that runs past a landscape of scrubby bushes and homes that appear half-built, with crude holes where the windows and door should be. The home where the orphans live is similarly unprepossessing: a pair of concrete houses built on a lumpy plot of land, all enclosed by an eight-foot wall topped with coils of barbed wire. (Before the wall was built, the house was burglarized by thieves who took everything from the home’s small TV to its cups and plates.)

Sitting under a shade structure of woven grass, Achon pulled out a small tub of orange-flavored Gatorade mix that he brought over as a treat for the kids, and sent one of the boys to fetch a bowl for mixing it. He then handed out a stack of black-and-blue plaid shorts, bought on sale at the Nike Employee Store for $4.99 each. When Achon and Fee assembled a dozen kids for a photo, the effect was at once goofy and solemn: two rows of skinny boys in matching oversized shorts, bare chests puffed out, staring soberly at the camera. “This is beautiful, Julius,” Fee said. Achon nodded. As the kids dispersed, I asked him what he was thinking. Achon paused. “That it’s a good day,” he said finally. “It’s been so hard...” He grew quiet, then added, “I just thank God for this.”

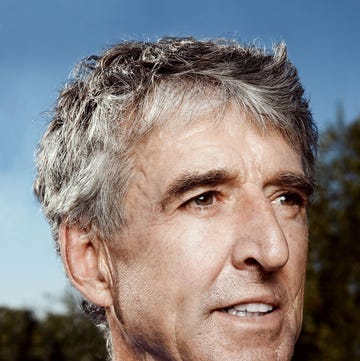

OUT OF AFRICA been easy. Not long after Achon set his NCAA record, at age 19, his mentor and coach John Cook left the university to start a private coaching practice. The departure devastated Achon, for whom Cook had been as much a father as a coach. Achon had often spent evenings at the Cooks’ house, and the coach had sometimes given him clothes for school, or extra pocket money. “When he left, things really went bad for me,” Achon said.

Around the same time, the war in Uganda was escalating, and rumors spread that the LRA was torturing villagers: Men who resisted conscription were reportedly being butchered and then boiled, and families forced to eat the stew. Unable to contact his parents, and fearing that they might have been killed, Achon dropped out of GMU and flew back to Kampala.

Though the trip relieved his fears—Achon found his parents alive and well—it proved disastrous in other ways. Shortly after Cook left, Achon had lost his NCAA eligibility by competing in a professional race in Japan. After dropping out, his student visa also expired, leaving Achon stranded in a war zone. Desperate, Achon signed a contract with a running club in Portugal: the only job he could find that paid better than a job in Uganda. “I didn’t want to go back to where I came from,” Achon told me, about the decision. “I wanted to keep going forward.”

In that Achon succeeded, making it to the semifinals of the 1500 meters at his second Olympics, in Sydney in 2000. Still his situation was far from ideal. The basement in Lisbon where he lived was unheated; Achon remembers huddling in his bed for warmth after he returned from a workout. And the club’s race schedule was rigorous. As a contract runner, Achon kept a punishing schedule that wore on his knees.

Achon stayed in contact with Cook after he left GMU, and in December 2003, just two months after Achon had stumbled across the orphans in Lira, Cook emailed him with a job offer: a chance to serve as a pacer to elite runners at Nike, where Cook now worked. In turn, Achon would be paid a salary of $1,600 a month—almost five times what he was earning in Portugal. “That moment changed my life completely,” Achon told me.

Achon moved to Portland shortly before Christmas, with his wife, Grace, whom he’d married in 2002, joining him not long after. But life in the United States proved more difficult than expected. The terms of Grace’s immigration visa forbade her from working for two years, and Achon’s $1,600 salary, which had sounded lavish overseas, barely covered the couple’s expenses. Though Achon still managed to send home $100 a month to cover the orphans’ food, he soon began to fret about the fact that they weren’t attending school. Reluctantly, Achon contacted his brother Jimmy to propose a deal: If Jimmy would quit college, Achon would use the money he had been contributing toward Jimmy’s tuition to pay the orphans’ school fees. In the meantime, he suggested, Jimmy could return to Lira to help care for the orphans, taking over from his mother and father, who were worried about losing their farm, and wanted to return to Awake.

Jimmy agreed, and in March moved into the house in Lira, still just a small grass hut. Not long after, Achon qualified for his third Olympics, only to learn, a few weeks later, that his mother had been shot by LRA soldiers on the road outside the village. After the shooting, Achon told me, his father tried to contact him, hoping that he could provide the $1,500 needed to take her to the hospital and pay for care. Still new to Portland, Achon didn’t have enough to send, and was afraid to ask Cook for yet more help. While he tried to raise the cash, his mother slowly bled to death. She died three days after being shot.

Devastated, Achon continued to struggle through his work as a pacer, and at night would return home and weep. “My wife would hold me on her lap like a baby,” he said.

At Cook’s insistence, he also tried to continue his Olympic training, but was eventually forced to withdraw. In retrospect, Cook says, he regrets not taking Achon’s bereavement more seriously. “I told him, ’I think your mother would be proud of you. Work your way through this. You’re on the cusp of being a great world-class runner.’”

Instead, Achon’s career gradually collapsed, after he injured his knee in a race and later hurt his back in a car accident.

Achon also remained haunted by the death of his mother. Guilty about his failure, he spent the next three years saving as much as he could to send home. Then, in January 2007, a former coworker invited Fee and his wife to have dinner with Achon, who had taken a second job coaching high school track on the weekends. When Fee learned that Achon was saving what he could from his salary to send to Awake, he and his wife decided to contribute $500 each quarter. “We said, ’We’ll see where this goes,’” Fee recalled.

Over the next year, Fee and Achon met up often on the Nike campus in Portland. At the time, Achon was making roughly $24,000 a year, and living in what Fee remembers as “an awful little moldy, one-bedroom apartment.” “It was at that point that I realized: They have nothing,” Fee said.

Not long after, Fee retired from his job in the medical industry, in part so that he could devote more time to helping Achon’s tiny foundation, the nonprofit Achon Uganda Children’s Fund. In 2010, at Achon’s urging, Fee also traveled to Uganda for the first time. He was initially reluctant. “I said, ’Why don’t I just write you a check?’” Fee said. “It was one of those moments. Like ’Okay, how involved do you want to get?’”

Fee remembers the 17-day trip as “shocking.” Writing in the foundation newsletter, he described the deplorable conditions in many Ugandan hospitals, where patients often slept on mats on the floor, and noted that the district hospital had recently lost its only doctor, leaving 85,000 without medical care. Even a campaign to combat a recent polio outbreak was struggling when the refrigerator needed to store the vaccine broke down.

At one point during that initial trip, Achon took Fee to visit the home where the orphans lived. They arrived to find one of the children—Monica, a tiny girl of 4 years—feverish and ill. Suspecting malaria, Achon took the children to the local clinic to be examined. The 12 tested positive for the parasite, so the next day, Achon and Fee took the sick children back to the clinic for treatment, and that night went into town to buy mosquito nets for the children’s rooms. The experience stayed with Fee. “We’d taken care of 12 kids with malaria, and gotten mosquito nets for them,” he said. “All for $150. I thought, It’s so little, and it makes such a difference.”

In 2009, Fee and Achon began talking about expanding the charity in order to build a medical clinic for the village. With Fee’s help, Achon began giving talks at church groups and Rotary clubs. Still, getting the project off the ground proved challenging. Fee admitted that he came to Africa with little experience of how developing countries operated—or even of what they were like. He was amazed by the difficulties presented by working in Uganda. Achon, he noted, was “paranoid” about money, and with good reason. “I consider myself a seasoned, experienced businessman,” he told me. “And I think I’m a good judge of character. What I’ve found is that my radar is useless here. Everybody who’s cheated us, I haven’t seen it coming.”

By the time of the groundbreaking last spring, the situation had improved. The day after Achon had arrived in Uganda, he had received an email from Nike reporting that a recent fundraiser had brought in $34,500, almost enough to cover the rest of the construction costs—though not the cost of equipment and staffing. Though it was 3:30 a.m., Achon promptly woke up Fee. Too excited to go back to sleep, they spent the rest of the night tinkering with the plans for the clinic. As Fee recalled: “I told him, ‘Julius, we’re actually going to do this!’”

THE NEXT DAY, WE DROVE NORTH to Awake. Though the village is only 42 miles away, the road is rough, a rugged route that winds past cows with towering horns and tethered goats left to graze by the side of the road. This is the road that Achon ran to reach the district championships when he was 13, and the memory animates him. Five miles outside Lira, he recalled, where the dirt road merges into asphalt as it enters the city, is where he first encountered pavement. In the heat, he said, the tarmac seemed to shine “like a river.” “But then I stepped on it, and it burned my feet like—ai!” he said and laughed.

Determined to measure exactly how far he ran as a young boy, Achon kept checking the mileage on the car’s odometer as we drove. In the heat of the day, the landscape looked desolate: a vast sandy plain pimpled with oversized anthills and low scrubby bushes. Since the war, he said, the village has been “like the beginning of the world; nobody has anything.” The last few miles into Awake, the land appears so deserted that I can’t even figure out where the village is. Achon laughed. “This is the village!” he said. Though the land looks like empty bush, he said, it actually contains hundreds of sparsely scattered farms. “When you call a meeting, a thousand or more come from nowhere,” he added. “There is no empty land here.”

Parking in the shade of a mango tree he had planted as a boy, Achon led me to the remains of the hut where he grew up. With the sun beating down, even the short walk was sweltering, like standing under a broiler. As Achon peered into the hut’s small space—four clay walls roughly five feet high, now mostly overgrown with weeds—he seemed briefly taken aback. As children, Achon and his siblings slept on pieces of stiffened cowhide, laid on dirt that had been smoothed flat with a paste made from cow dung. In the rain, Achon recalled, the grass roof often leaked—water dribbling in from holes where his mother had pulled out a straw to light the fire under the cookpot.

In the two decades since then, not much has changed. Talking later, Achon told me that he is alarmed by Uganda’s birth rate, and by the cycle of poverty it perpetuates. He is also troubled by the educational situation. Even now, he observed, children from the village can’t start school until age 8—a full year behind children in larger cities—because the walk to the schoolhouse is so far. That delay compounds other disadvantages, like the lack of basic supplies like pens and chalk, and limited facilities. When he was growing up, Achon recalled, 70 kids would often be crammed into a single room. “It’s packed,” he said. “You sweat.” Because there were no desks, students sat on the dirt, which was littered with old fruit peels and lumpy with anthills. Achon shook his head. “Little black ants,” he said, frowning at the memory. “They bite. They used to fight me every day.”

After finishing the medical clinic, Achon says, he would like to raise money to build a village school, and also wants to develop a sports program to help children who remain traumatized by the war. “When you run,” he said, “it helps you forget.”

From the hut, Achon drove to the site of the new medical clinic, located on a small clearing in the scrubland a stone’s throw from the current home of his father, Charles. In the distance, a crew of workmen were visible, laying bricks for the staff quarters under a baking sun.

Making his way through the stubby bushes, Achon examined the construction of the staff quarters. Built of brick, the rooms seemed tiny: just six feet a side. By local standards, however, they’re considered luxurious—a perk that Achon hopes will help the clinic attract and retain good doctors.

To persuade the village elders to support the clinic, Achon in 2010 convened an elder meeting following an all-village meeting, and arrived armed with a truckload of sodas—an unheard of luxury. After finishing a bottle, Achon recalled, the villagers would refill it with water, in order to extract the last faint drops of sweetness.

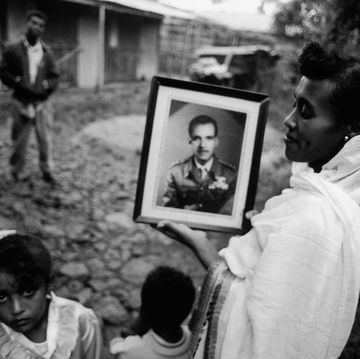

Back at the house, we joined Achon’s father in plastic chairs under the shade of a shea nut tree. Now a deacon in the local Pentecostal Church, Charles has a gregarious ease and a preacher’s talent for storytelling. But when I asked what he thought of Julius’s achievements, he fell silent, seemingly overwhelmed. Pressing his hands between his knees, he began, “To be picked, out of such conditions?” He paused, shaking his head in amazement. “He was lifted up by God.”

If Achon was lifted up by God, it soon became clear that others hoped to be lifted up by Achon. As news of our arrival spread, a growing number of villagers arrived from farms deep in the bush, including a barefoot woman, a former schoolmate from Achon’s childhood, carrying a year-old baby on her back. Kneeling at Achon’s feet, she explained that she was walking to the nearest clinic, five miles away, because her baby had been diagnosed with malaria. The infant now had to get a series of five shots, which together would cost 10,000 shillings, or about $5—more than she could afford. Could Achon help her? After handing her the money and watching her leave, Achon bowed his head and punched a fist into his palm. I asked whether the encounter had upset him. He said no, he was simply moved. “This small money she asked for,” he said, “I just kept thinking how little it was. How little it takes in this place to help people.”

That Pre Thing returned from the village in a buoyant mood—optimistic about the clinic, and glad to have seen his father—the next morning he seemed unhappy and withdrawn. He had gone for a dawn run along his old route, finishing at the bus park. There he had been recognized by a former schoolmate, who had yelled, “It’s Achon!” Mobbed by curious onlookers, Achon had had to deflect numerous pleas for money. Though the appeals weren’t new, their sudden intensity had shaken him.

“Now that they know I’m here, people are coming,” Achon said, briefly resting his forehead in his hands. “‘I always say to Jim Fee: There are 33 million people in Uganda, and everybody needs help.”

Though Achon is resolute about keeping his charitable efforts focused on the clinic and other projects ‘that help many people, and last from generation to generation,’ the role of benefactor wears on him. Not long after Achon got back, two men stopped by the hotel looking for him. Like Achon, both had competed at the district championships in 1990 and performed well enough to be offered scholarships to Makarere College School in Kampala. Unlike Achon, they had turned the offer down—too fearful of leaving their families, and moving to a city where the common language was English. In the 20 years since, they have remained poor, and one of the men has since contracted HIV. Achon took both men to lunch, but was alarmed by his companion’s wasted frame. “He was so thin,” Achon said afterward. “Very hollow. Looking at his chest, you can see his ribs.” He sighed uncomfortably. “When I’m here,” he admitted, “I want to go.”

The encounter seemed to highlight the narrowness of Achon’s own escape: the thin thread of chance that had sustained his ambition. Back in Kampala, I spoke with Christopher Banage Mugisha, the sports master who had scouted Achon at the District Championships 22 years before. If Mugisha hadn’t seen him run, I said, it seemed likely that Achon would have stayed on the farm with his family, married, and never have left the village. Mugisha agreed. “There are those who have the potential but do not get noticed,” he said with a shrug. “And there are those who have the potential, and also get noticed, but who are not willing to take the risk. To have all three—the potential, the luck to be noticed, and the willingness to take the risk—that is the story behind the success of Julius Achon.”

Perhaps with discipline in mind, the next morning Achon decided to assemble the orphans for a group run. At dawn, the air was muggy and cool, filled with the trill and buzz of invisible insects. In the distance, low peaks rose out of a white mist. Once the children had mustered in the courtyard, we departed at a jog, the youngest children racing to keep up with the older ones, who proceeded slowly. After half a mile, we turned off at a makeshift dirt track, where Achon led the group through stretches and plyometrics. “I don’t think they’ve been running very much,” Achon said, dispatching the kids on a series of sprints. “Without someone to tell them, they get lazy.”

Visiting the village, Achon added, he had seen his own childhood in all its poverty: the kids in stained clothes that hadn’t been washed for a month. Though life at the compound is far from luxurious by American standards, it’s sufficiently comfortable that Achon occasionally frets for his charges. “Already they are forgetting the conditions they were sleeping in, the bad clothes they used to wear, how little food they used to eat,” he said. “I ask them: Remember the small grass hut we used to sleep in? Was there even electricity there for the nighttime?”

In many ways, this is an achievement. Achon has given his charges something that he himself never had: the small luxuries of a normal childhood. But comfort can breed complacency, while misery, perversely, was for Achon profoundly motivating. “When you run in such conditions, you have to be fast,” he said at one point. “Because you are running away from death.”

Because of this, Achon says, he now plans to have the children go to Awake on each school holiday to work on the farm. “For so long they have been eating good food, sleeping on soft beds,” he said. “These kids need to learn certain things.”

The fragile nature of good fortune is one thing that Achon has come to appreciate all too well. Two years ago, Achon lost his job as Salazar’s assistant during a round of budget cuts at Nike. He now works part-time at the Nike store on campus, earning $1,100 a month. Though the cut in salary was ruinous, Achon didn’t complain. Last spring, Fee recalled, Achon finally came to him, ashamed that he was finding himself too short of money to live. “We went through his monthly budget,” Fee said. “It was $2,000. Between rent and food and sending money home, he could no longer pay his bills.” Fee arranged for Achon to receive a small salary for his foundation work, but even with this, he told me, Achon remains obsessively frugal. “What’s astounding, to me, is that when he’s making so little, he’s still always carving some out to help people back home,” Fee noted. “It’s remarkably selfless.”

Still, it was hard not to wonder about the cost of Achon’s effort. Not long after returning home, the star Kenyan runner Samuel Wanjiru died from jumping out of a window—a possible suicide. Living in Kenya, Wanjiru had been constantly pressured for handouts. When I asked Achon what he thought of this, he sighed. “Such huge money he was making,” Achon said, shaking his head. “When I read that he grew up without a father...” He paused. “In Africa, growing up without a father is so difficult. You have nothing. You eat trash. You eat banana skins.”

Achon seems to have avoided this trap in part through circumstance; unlike Wanjiru, his career never brought in that much cash. At times, though, Achon’s austerity can seem less salutary and more traumatized: the product of a lifetime of deprivation and uncertainty. Even living in Portland, he noted, he eats just one or two meals a day, so that he stays prepared for periods of hardship. “I train myself,” he told me. “I treat myself in the United States like I’m in Uganda.”

This reflexive self-sacrifice also seems to reflect another conviction: that Achon’s improbable survival amid so much war and disease is a gift from God—a gift, in other words, that he needs to share lest it be revoked. “I’ve survived several deaths,” Achon told me at one point. He paused. “My dad would always tell me, ‘Do something for people, and God will spare your life.’”

Story Update · August 11, 2016

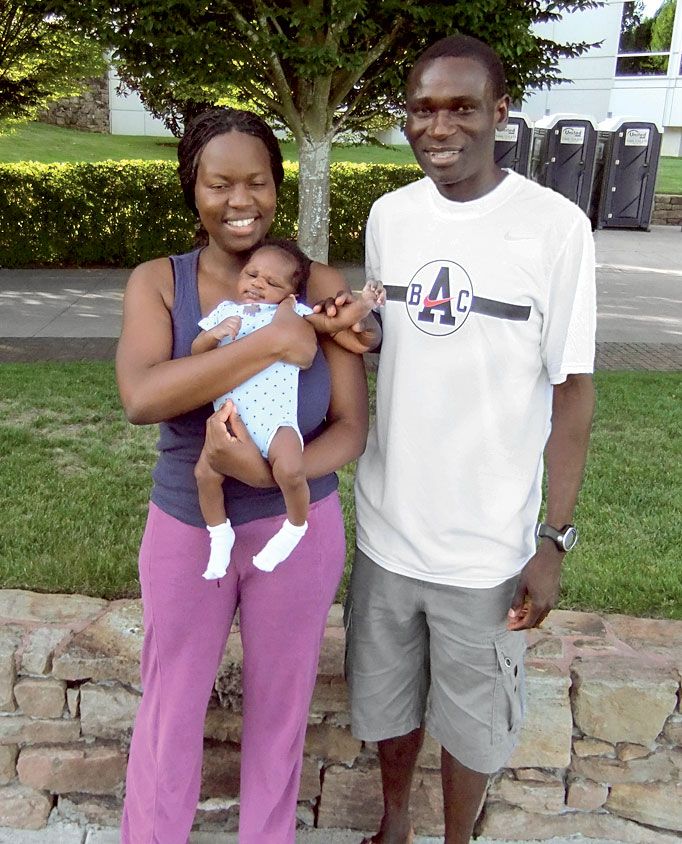

In the fall of 2012, the Kristina Health Center—named for Achon’s mother—opened its doors in Achon’s home village of Awake. It has since treated 24,000 patients. Construction recently finished on the center’s fifth building, named in memory of Jim Fee, who died in 2013 in a bicycling accident. Fee’s family remains fully involved in the Achon Uganda Children's Fund; Jim’s widow, Angela, is executive director, and his sons, David and Mike, are on staff. As for Achon, he and his family (his sons are 5 and 2) now live in the Ugandan capital of Kampala. In February, he was elected to represent his home Otuke district in the country’s parliament. “I came back from the U.S. because I wanted to take care of my community and country,” he says. “I have a bigger voice now.” A busier schedule, too. He makes the roughly 200-mile drive to Awake twice a month to oversee his foundation, and has partnered with Australian Olympic distance runner Eloise Wellings and her organization, Love Mercy, to support 40 Ugandan orphans (largely through boarding school sponsorships); their partnership also assists village women and their families through an innovative agricultural-loan program. Despite all his responsibilities, Achon still runs about five days a week, and even found time to collaborate on a recent book, The Boy Who Runs: The Odyssey of Julius Achon, with RW contributor John Brant. Says writer Jennifer Kahn, “I’m always, unfortunately, somewhat surprised and amazed by people who manage to escape circumstances such as what Julius did who still feel a very serious obligation to go back and try to help. You’d think it would be enough to try and get themselves out. But Julius was very committed to his village in Uganda.” –Nick Weldon